Most Agile DevSecOps conversations start the same way, and they answer what is DevSecOps vs Agile better than any definition: the sprint is moving, a scan fails, and nobody can say whether this should block the release or just create a ticket.

That’s the core gap decision system is meant to close. DevSecOps is a decision system for the delivery system: it defines where enforcement happens, who owns the call, and what evidence proves the call was made, so security outcomes are repeatable instead of negotiated under pressure.

Agile is different. Agile is a model for iteration: it optimizes how work flows from backlog to sprint to review, tightening feedback loops so product learning stays fast. The confusion shows up when engineers try to use Agile ceremonies to answer questions that belong to release governance.

In this guide, you’ll see both models side by side, map them across the SDLC, and walk through a practical blueprint for gates, evidence, ownership, and environments.

Agile DevSecOps: definition for software engineering teams

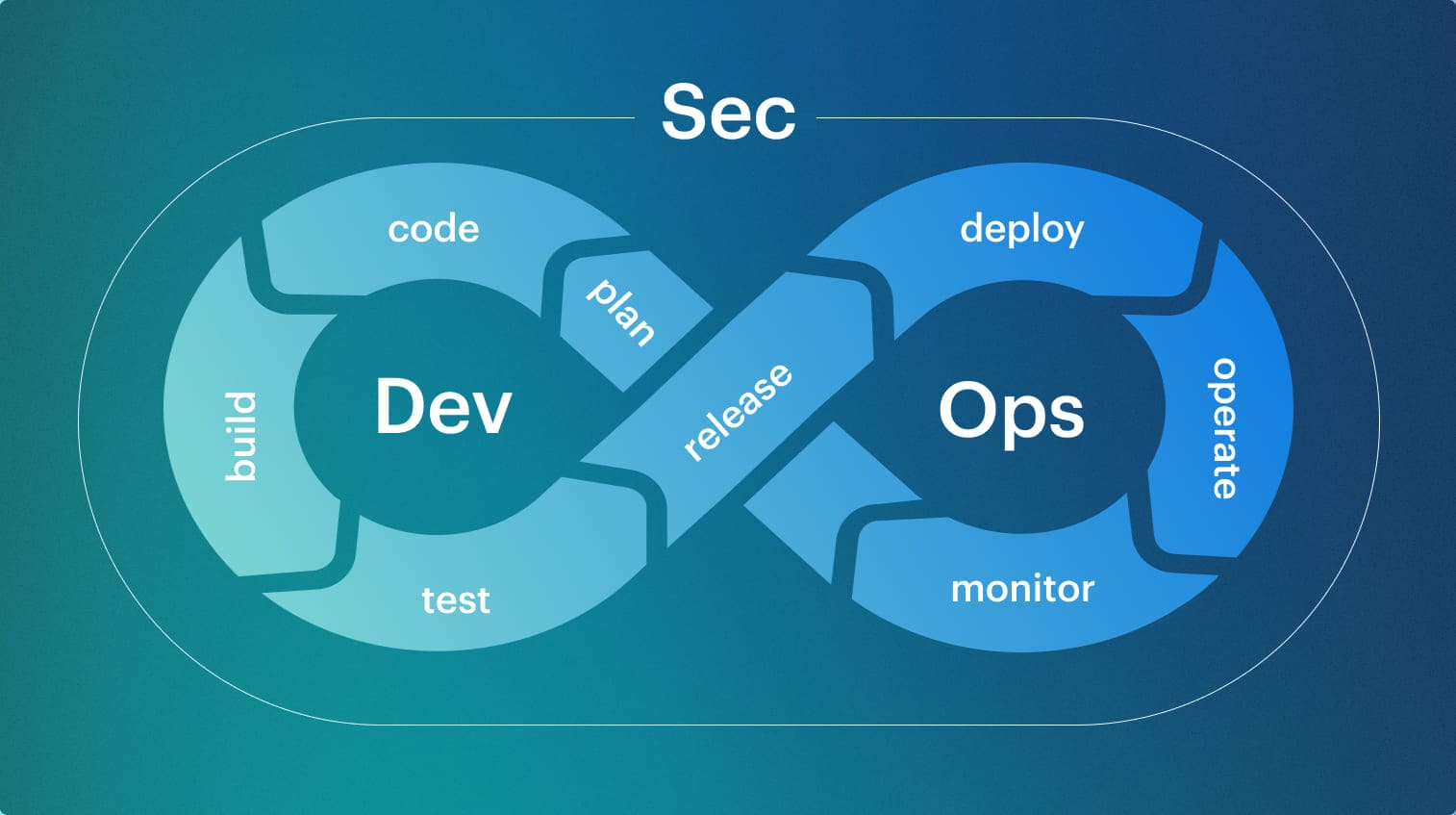

Agile DevSecOps makes sense once you separate responsibilities in the delivery system. Agile is the iteration model: it governs how work moves through backlog, sprint, and review.

DevSecOps is the decision system: it governs how release and promotion decisions are made when controls surface risk. Together, they form a delivery model where sprint cadence stays fast, but policy, ownership, and evidence keep promotion predictable.

DevSecOps definition: a decision system, not a toolchain

In software engineering, the question that matters is, “Does this block the release?” DevSecOps exists to make that answer consistent. Tools alone do not solve it in Agile delivery setups, because a scanner can only produce a finding, not a release decision. The missing layer is intent plus accountability. Policy intent states what is acceptable for this workload and environment. Thresholds define what blocks versus warns. Owners define who can approve an exception. Evidence links the decision to the change, the artifact, and the target environment, so a secure promotion path follows secure promotion rules.

The missing layer is intent plus accountability. Policy intent states what is acceptable for this workload and environment. Thresholds define what blocks versus warns. Owners define who can approve an exception. Evidence links the decision to the change, the artifact, and the target environment, so a secure promotion path follows secure promotion rules.

Agile is a feedback loop, not a release control model

Agile is a feedback loop that keeps work small, visible, and reprioritizable. It shapes the development process through refinement, planning, and review, but it does not define enforcement when a check fails right before promotion, because most engineers assume the delivery system will enforce whatever “done” means.

The combined model works when the Definition of Done and acceptance criteria include concrete security outcomes validated by gates and owned decisions, not ceremonies. Treat security practices as first-class requirements, and the sprint ends with “policy met, and evidence captured,” not “scans ran.”

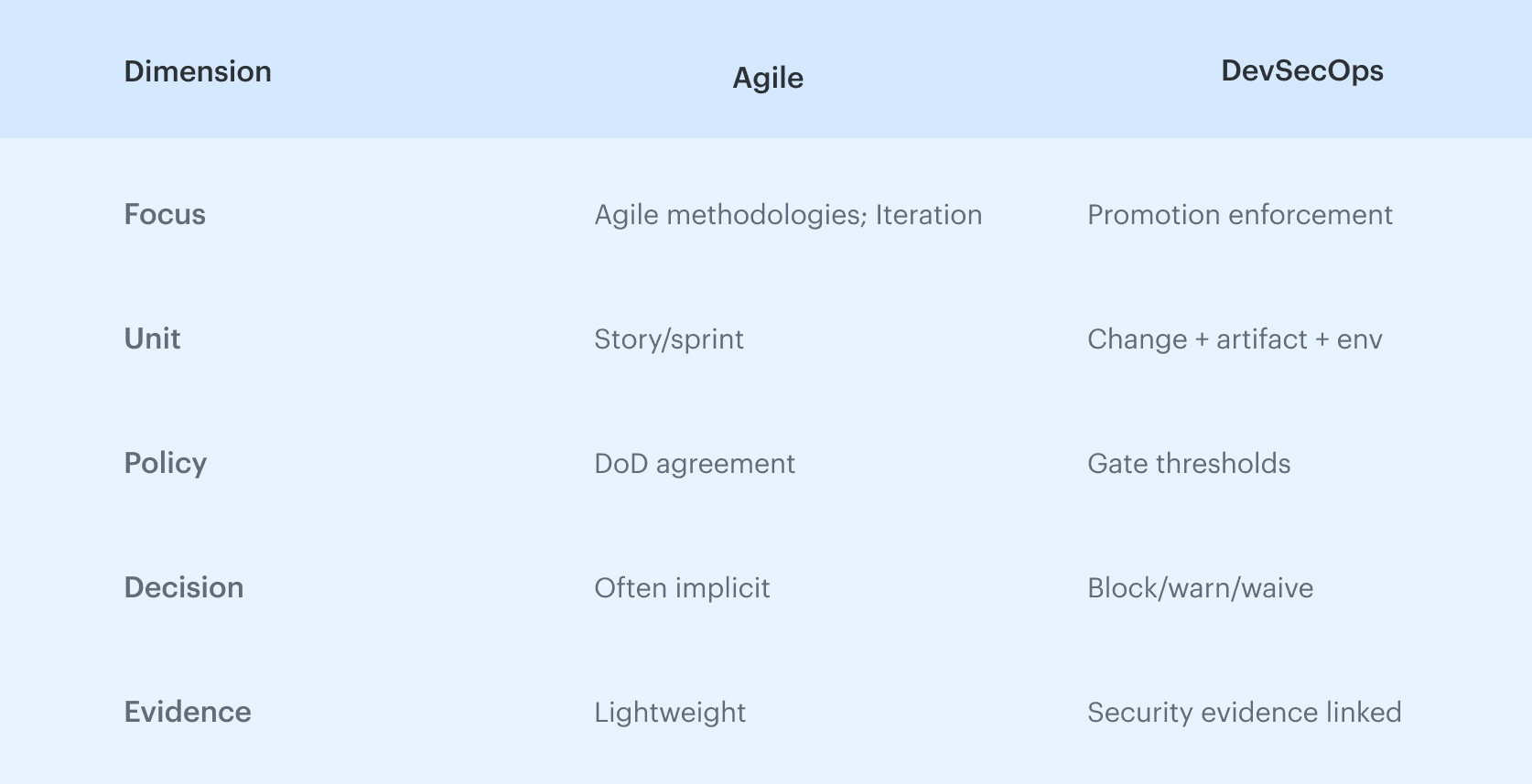

DevSecOps vs Agile: what changes in the development process

DevSecOps and Agile aren’t competing frameworks, but they answer different questions in the development process. Agile optimizes how work is shaped and validated through fast feedback, while DevSecOps defines how promotion decisions are enforced once signals show risk, with clear ownership and evidence.

In Agile vs DevSecOps, the hard part is knowing which question you are answering: prioritization or promotion.

Difference between Agile and DevSecOps

Agile lives upstream: backlog → sprint → review → feedback. It helps to decide what to build next and how to learn quickly. DevSecOps sits on the path to production: it adds gates and rules that define what “safe to promote” means for this change, this artifact, and this environment.

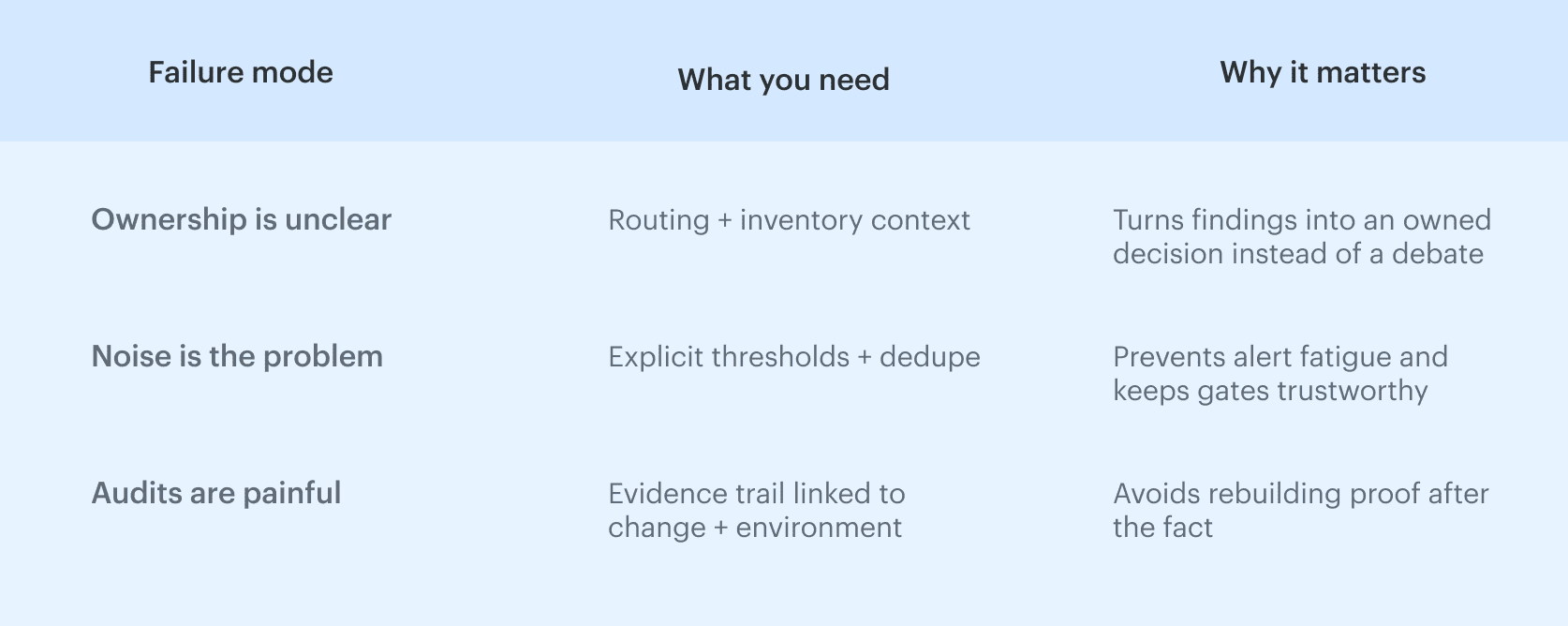

When DevSecOps is treated as tooling instead of enforcement, security becomes a recurring argument about severity and exceptions. The fix is decision ownership (who can waive, who must remediate), thresholds (block vs warn), and evidence that links the call to the change, so management can trust the outcome and the business can ship without guessing.

DevOps vs DevSecOps: where security becomes a gate

DevOps automates build, test, and deploy to reduce friction. DevSecOps extends DevOps with policy-backed controls, so the default path is secure and exceptions follow an explicit workflow.

“Shift-left” helps, but without runtime validation and drift detection, owners approve intent and then lose confidence that production still matches it, which is why operating practices matter as much as scans.

DevSecOps and Agile only align when promotion decisions are explicit, and the sprint does not become the approval workflow. Orgs repeat the same mistakes when they blur responsibilities:

Orgs repeat the same mistakes when they blur responsibilities:

- Assuming DevSecOps is a tool swap, not a decision model

- Turning ceremonies into approval gates

- Optimizing for fewer findings instead of clearer criteria

- Recreating exception workflows in Slack under pressure

- Treating security as “shift-left only” and ignoring runtime drift

- Expecting management to arbitrate every release decision

DevSecOps and Agile across the software development process

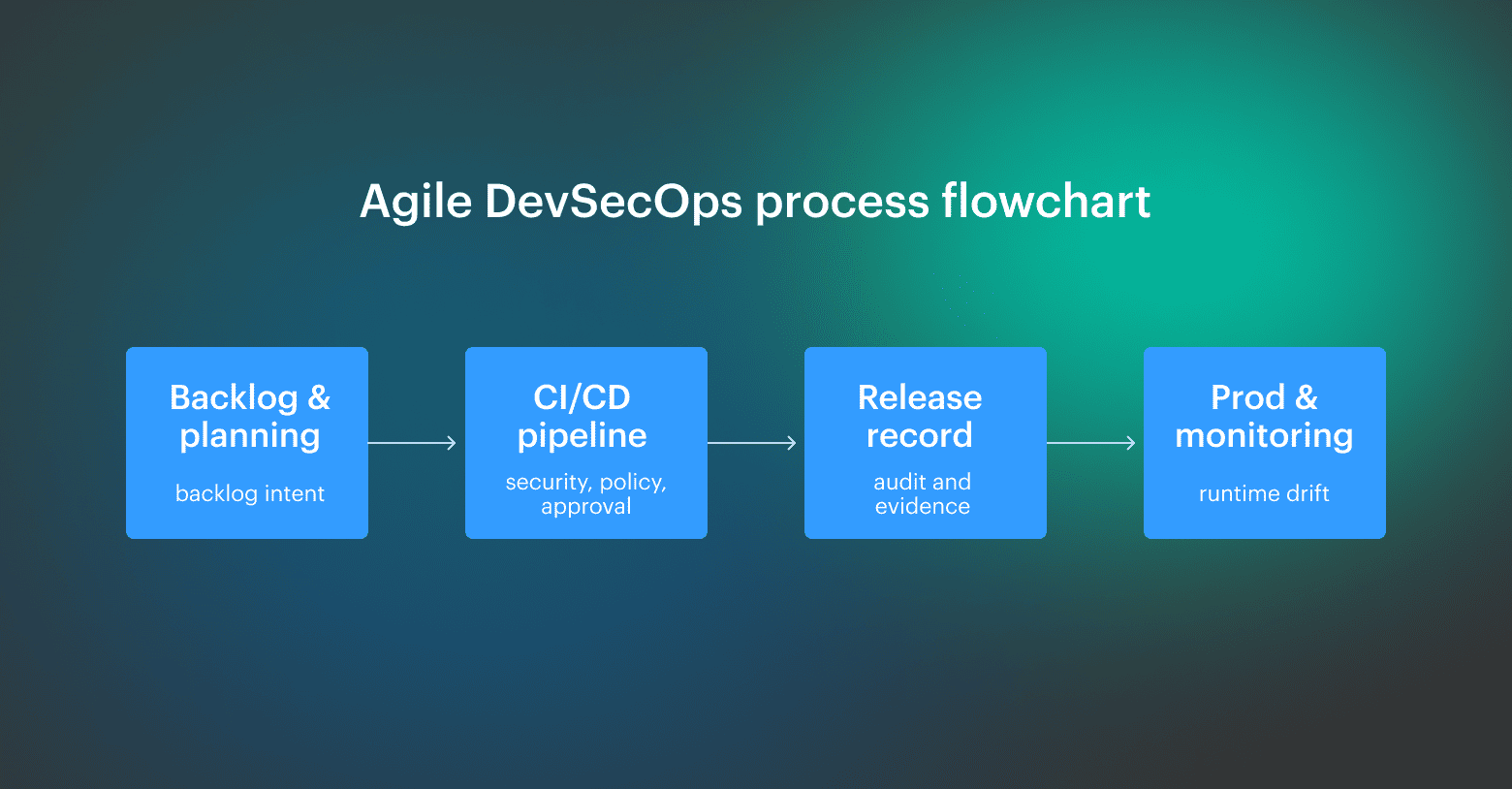

Agile and DevSecOps connect cleanly when you treat them as two views of the same system: Agile governs how work is selected and validated, and DevSecOps governs how that work becomes eligible for promotion. The goal is a single thread from backlog intent to a release record, so you can explain what was approved, what changed, and why it moved forward.

The goal is a single thread from backlog intent to a release record, so you can explain what was approved, what changed, and why it moved forward.

Agile methodologies and security practices in the same backlog

Security work belongs in the backlog where tradeoffs are visible. Threat modeling fits into refinement while the scope is still negotiable. Dependency upgrades are delivery work and should be planned like any other change. Security debt is also debt, which means it needs sizing, owners, and a policy for when it blocks versus when it becomes scheduled remediation.

The failure mode is splitting this into a separate track where nobody owns outcomes. Security practices stay sustainable when they are expressed as backlog items with acceptance criteria, and when owners can see how those items map to enforcement later in the pipeline.

From code to release: mapping checks to the software development process

The software development process becomes auditable when you connect acceptance, enforcement, and evidence without rebuilding the story later. The Definition of Done and acceptance criteria define intent. CI gates catch regressions before promotion. A release record captures what was built, what checks ran, who approved exceptions, and where the artifact was deployed.

This is where the enforcement model and the iteration model need a shared contract. A change in code should carry metadata (commit, author, diff) into the pipeline, and the artifact should carry the evidence forward, so “safe to promote” is tied to a specific version. That traceability also protects shared resources, because ownership and scope stay explicit as environments evolve.

Read also: What Breaks in Delivery When DevSecOps vs SDLC is Misunderstood

Security gates in Agile development

Security gates work in Agile development only when they behave like product constraints, not like surprise audits at the end of a sprint. The point is to keep cadence stable by making decisions predictable: which checks are fast signals, which are deeper validations, and who owns the call when something fails.

Security testing that fits sprint cadence

Security testing should be staged. In Agile development, the CI lane needs fast signals that catch obvious regressions early, while deeper testing runs where it can be tied to an artifact and a promotion decision. SAST, secrets checks, and dependency hygiene are valuable early, but they only help if thresholds are explicit and tuned to change type; teams drown in noise.

Severity thresholds are the difference between enforcement and alert fatigue. Define what blocks versus warns, and tie it to risk: a dependency bump is not the same as a privileged IaC change, and a docs-only commit should not trigger the same gate as a production-facing code path.

These practices keep the pipeline trustworthy and keep security outcomes consistent.

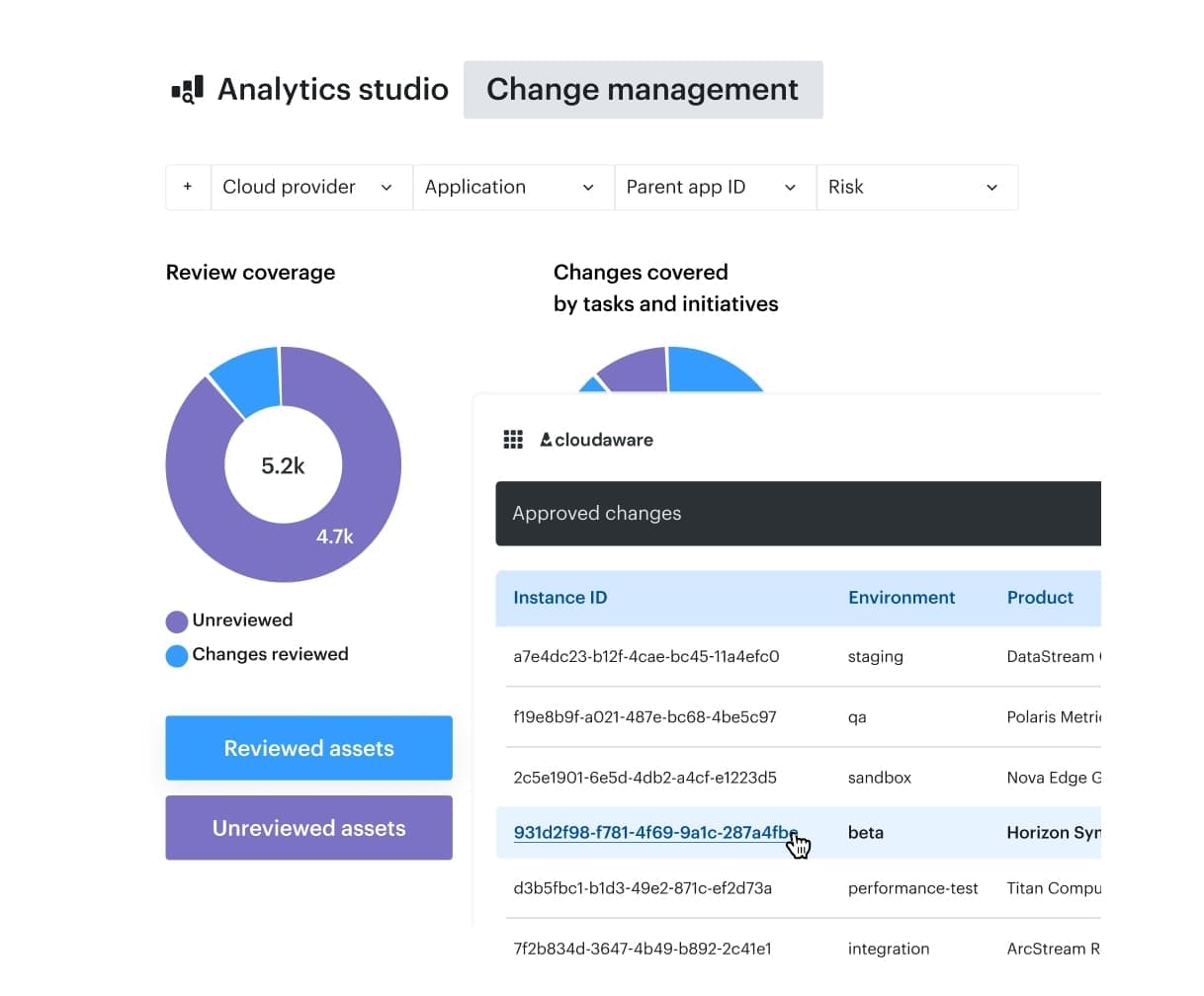

Evidence, management, and accountability: who approves what and why

Ownership is the scaling problem. Someone must be able to say “block,” “warn,” or “waive,” and that decision needs to route to the right owner without becoming a release meeting.

Management needs traceability: what was approved, by whom, when, and for which environment, because the business impact of exceptions is not the finding itself, but the untracked risk that ships repeatedly.

Exception debt is where systems quietly fail. If waivers do not expire and return to the backlog with clear owners, the same issues reappear, customers lose confidence in controls, and security becomes performative.

In Agile development, the goal is a reliable audit trail that ties decisions to versions and environments:

- Change metadata (commit, author, diff) linked to the artifact version

- Policy outcome per gate (block, warn, waive) with the applied threshold

- Security testing results tied to the artifact digest (and rerun policy if needed)

- Approval record for exceptions (owner, timestamp, rationale, expiry)

- Deployment record (environment mapping, release ID, promotion path)

- Post-promotion validation link (drift or verification result)

Read also: DevSecOps Roles and Responsibilities (Who Does What and How Teams Are Structured)

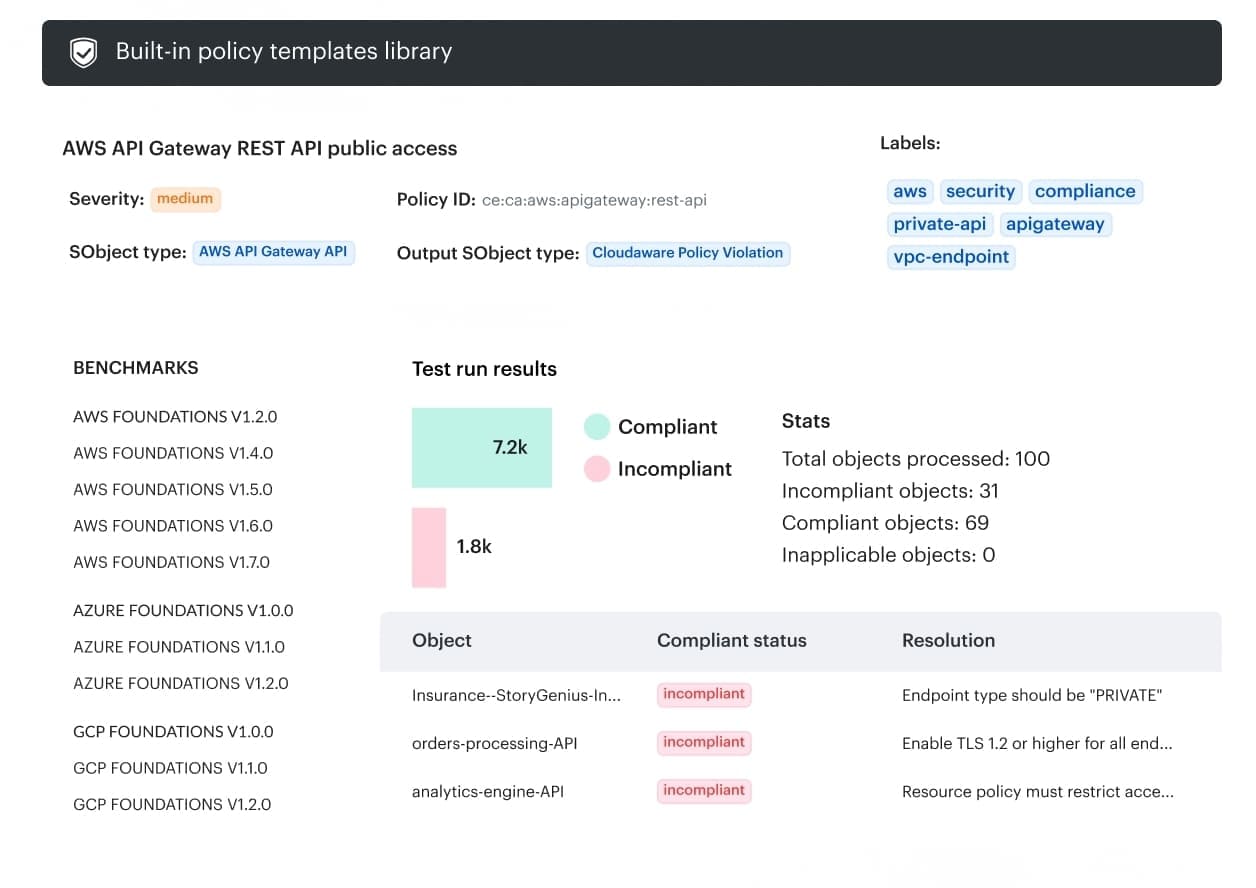

Policy controls that work at every stage

Policy only scales when it stays stable across every stage of delivery, because a DevSecOps Agile environment changes faster than ad hoc rules can keep up. The goal is one policy contract that defines enforcement points and required evidence from PR through runtime, so owners can promote without renegotiating rules on each release and the default path stays secure.

The DevSecOps approach: policies that don’t collapse under iteration

Policy-as-code works when you separate intent from implementation, and then enforce it at predictable points:

- PR checks: validate declared intent and obvious violations before merge

- Build checks: bind results to the artifact (what was built and what was proven)

- Deploy gates: verify eligibility for the target environment, not “any environment”

- Runtime validation: confirm what is running still matches what was approved

- Thresholds + waivers: treat them as first-class controls with owners and expiry, not informal shortcuts

The DevSecOps principles are the enforcement layer behind that list: make blocking criteria explicit, route exceptions to a named owner, and preserve evidence so decisions can be replayed without debate. That matters when a customer audit request arrives, and customers ask for proof of what was enforced, not a story about what “usually happens.”

That policy contract holds only when policy intent is evaluated against real infrastructure context, not abstract assumptions about what “production” means, and Cloudaware provides that context layer by mapping environments and ownership to actual resources, so the same policy can be enforced consistently as the system changes.

Connecting platform signals to delivery decisions

DevSecOps breaks down in a DevSecOps Agile environment when the DevSecOps platform is reduced to “alerts in a dashboard.” Findings arrive, but the system cannot answer basic questions like who owns this workload, which environment is affected, and whether the artifact in production is the one that was approved.

Without asset and ownership context, signals stay noisy, and teams default to manual triage, which slows delivery and creates inconsistent outcomes for the business.

A control plane becomes valuable when it links the full chain:

- Change metadata → workload → environment → owner → policy outcome

- A “critical finding” becomes a routed decision with a clear next step, because the right owner sees the right scope

- Evidence stays attached to the artifact and the promotion record, so the decision is reproducible

- In customer conversations, traceability turns “we think it’s handled” into “here is the decision, the approval, and the deployed version”

- When a customer asks why something shipped, the platform can show whether it was blocked, warned, or waived, and by whom

Approaches range from point tools to control planes, but the goal is the same: reduce noise through dedupe and routing, then shorten remediation with clear SLAs that engineering leaders can trust. That operational clarity is the difference between a secure answer to a customer escalation and an internal guess that turns into business risk.

At that point, the problem is no longer scanning quality. The problem is missing context for routing and scope. Cloudaware enriches findings with ownership and environment context, so triage becomes a routed decision.

Solutions that teams can run consistently

Most efforts fail when tools are chosen by feature lists instead of failure modes, because Agile and DevSecOps implementation breaks when ownership and thresholds are implicit. DevSecOps and Agile stay compatible when exceptions expire, findings become backlog items, and gates update after incidents. Tool sprawl happens when each scanner creates its own workflow, so the organization ends up with parallel definitions of “block,” “warn,” and “waive,” none of which map cleanly to promotion.

DevSecOps and Agile stay compatible when exceptions expire, findings become backlog items, and gates update after incidents. Tool sprawl happens when each scanner creates its own workflow, so the organization ends up with parallel definitions of “block,” “warn,” and “waive,” none of which map cleanly to promotion.

Some teams follow GitLab’s framing of a single-toolchain path, but the brand is not the point. The point is connecting gates, evidence, and ownership tightly enough that release decisions stay consistent even when the system changes.