The DevSecOps lifecycle is usually shown as an infinity loop, but the diagram alone doesn’t explain how security decisions are enforced as software moves through delivery. What matters in practice is where controls exist, who owns them, and what evidence remains after each step.

This article treats the DevSecOps lifecycle as a set of specific decisions applied to the software delivery process. It shows how security fits into code, build, test, release, and runtime without assuming a specific platform or DevSecOps toolchain. Each phase is described in terms of gates, ownership, and outputs rather than concepts.

In this article, you will learn:

- How the DevSecOps lifecycle operates as both a loop and a process flow

- Where security checks, approvals, and policies are enforced in the pipeline

- What completion criteria look like at each lifecycle phase

- How roles and ownership are distributed across teams

- What evidence and metrics demonstrate that the lifecycle is working as intended

DevSecOps lifecycle explained in one loop

The DevSecOps lifecycle is not a replacement for the software development lifecycle. The SDLC defines how software is built, while the DevSecOps lifecycle defines where security decisions are made and enforced across that flow. It overlays the SDLC with controls that repeat every time code changes, infrastructure changes, or environments drift. This DevSecOps lifecycle diagram shows where decisions and gates are enforced.

This DevSecOps lifecycle diagram shows where decisions and gates are enforced.

The infinity loop exists because security decisions do not end at release. A vulnerability found in runtime feeds back into backlog, code, tests, and policies. A misconfiguration detected in production changes future deployment gates. The loop models continuous decision reuse, not continuous scanning.

This is where DevSecOps differs from “DevOps plus security tools”: tools only generate signals, while the lifecycle defines enforceable decision points that determine when a build is blocked, a release is approved, or a runtime change requires action.

The loop connects those decisions so they remain consistent over time, even as teams, services, and pipelines change.

Read also: What Breaks in Delivery When DevSecOps vs SDLC is Misunderstood

DevSecOps infinity loop: how the cycle actually works

The DevSecOps infinity loop describes how the same security decisions are applied repeatedly as inputs change, not how often pipelines run. Code changes, dependency updates, infrastructure drift, policy updates, and runtime findings all invalidate earlier assumptions. The loop exists to make those decisions reusable, consistent, and enforceable across time.

From an engineering perspective, the loop connects delivery stages through shared control points. A decision made at build time must still hold at release. A runtime violation must influence future builds. Without the loop, security becomes a series of disconnected checks with no memory.

Why the loop never really “ends”

Security decisions expire when context changes. The loop continues because:

- New commits change application behavior

- Dependency updates change supply-chain risk

- Infrastructure drift changes exposure

- Incidents and audit findings change acceptance criteria

Each of these feeds back into backlog priorities, pipeline gates, and policy rules instead of living in isolated reports.

Where security decisions live inside the loop

Security lives at enforceable decision points, not at a position on a timeline:

- When code becomes a build artifact

- When an artifact is promoted to release

- When a release runs in an environment

Each point produces a binary outcome: allow, block, or require approval. The loop ensures those outcomes are re-evaluated whenever conditions change.

Read also: 4 DevSecOps Implementation Steps That Hold Under Release Pressure

DevSecOps process flow from commit to production

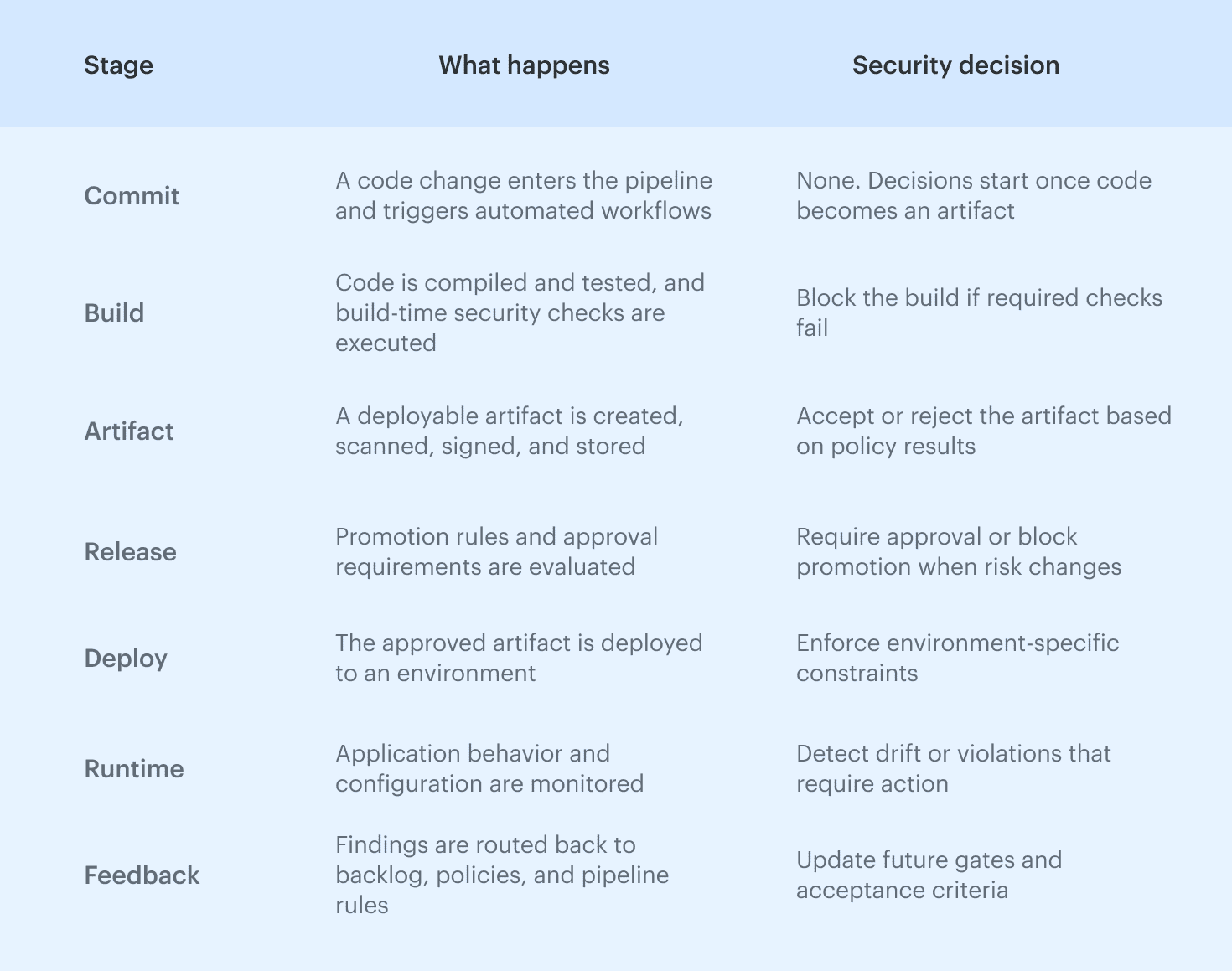

The DevSecOps process flow describes how a change moves through the pipeline and where security decisions are enforced along the way. Each transition from commit to build, build to artifact, and artifact to deployment creates a point where risk is evaluated and a clear outcome is required. Nothing is added later. If a control matters, it sits directly in the DevSecOps flow.

This view is intentionally linear. It makes it clear where a build can fail, where a release can be stopped, and where runtime signals must feed back into earlier stages. Platform and CI/CD teams use this model to keep pipelines understandable as they grow, without turning security into a parallel process that no one owns.

End-to-end flow: code, build, artifact, deploy, runtime, feedback

Security enforcement pattern:

Security enforcement pattern:

- Automated checks run where results are deterministic, mainly during build and artifact creation.

- Approvals are limited to transitions where risk changes, such as release or environment promotion.

- Policies define allowed and blocked paths to avoid case-by-case exceptions.

Read also: 15 DevSecOps Tools - Software Features & Pricing Review

Mapping the DevSecOps lifecycle to the software development lifecycle

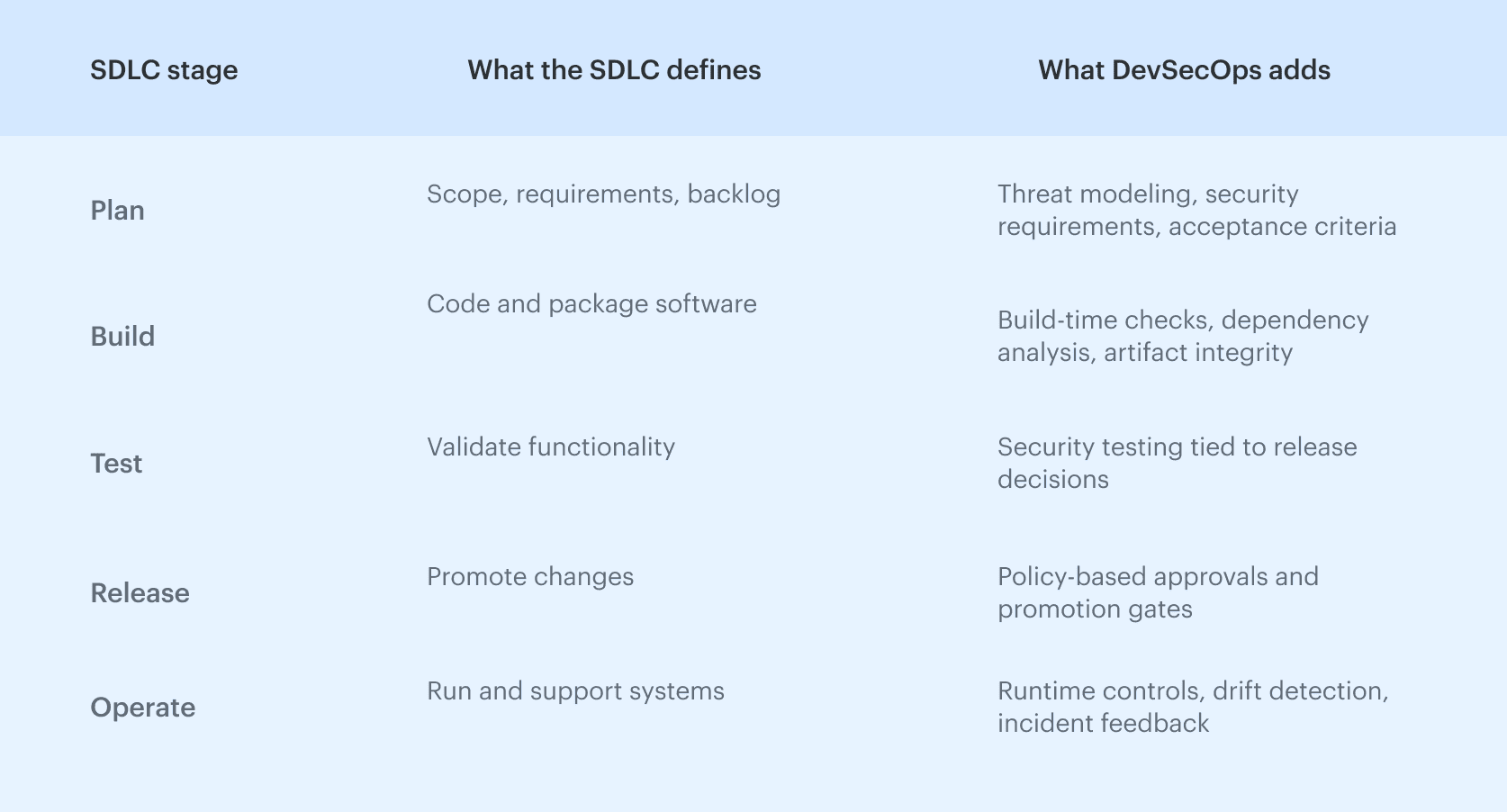

DevSecOps is not a separate software development lifecycle. It is a control and decision layer that sits on top of the SDLC your teams already use, whether that SDLC is iterative, incremental, or release-driven. The delivery stages remain the same. What changes is how security decisions are introduced, enforced, and carried forward as those stages repeat.

There is no single best software development life cycle in DevSecOps. DevSecOps adapts to existing SDLC models by adding gates, policies, and feedback loops where risk changes, rather than redefining how software is built.

SDLC to DevSecOps mapping

This mapping is what allows teams to adopt DevSecOps without rewriting their development process. The SDLC continues to define delivery mechanics, while the DevSecOps lifecycle defines where security decisions are made and how they persist across change.

This mapping is what allows teams to adopt DevSecOps without rewriting their development process. The SDLC continues to define delivery mechanics, while the DevSecOps lifecycle defines where security decisions are made and how they persist across change.

Read also: DevSecOps Architecture (A Practical Reference Model Teams Actually Use)

Phases of DevSecOps: what actually happens at each stage

The DevSecOps lifecycle is usually described in phases or stages, but the important part is not the names. What matters is that the same DevSecOps processes repeat at each step, even though the controls and owners change. Planning, building, testing, releasing, and operating all follow the same pattern: define expectations, enforce a decision, and record evidence.

The phases are checkpoints along a single delivery path where risk is reassessed as context changes. A design decision made during planning influences build gates. A runtime finding updates test coverage and policy rules. Each stage feeds the next, and none of them stands alone.

Below, each DevSecOps phase is described in practical terms:

- What decisions are made

- Where enforcement happens

- Who owns the outcome

- What “done” looks like before moving forward

Read also: DevSecOps Framework in 2026 - NIST, OWASP, SLSA Explained

Phase 1. Plan: DevSecOps planning before code exists

This stage exists to make later enforcement possible without manual reviews or last-minute exceptions. If a decision is not made in planning, it will be guessed later by a pipeline, a reviewer, or an auditor.

At this point, teams decide:

- Which services and environments are in scope

- What security requirements apply to them

- Which risks are acceptable by default

- Who owns those decisions

Threat modeling at this stage is lightweight and practical. The goal is not to document every possible attack, but to identify assumptions that must hold true later. Security requirements and acceptance criteria are written so they can be checked automatically during build, release, or runtime.

What “done” means in the planning phase

- Scope and ownership are explicit and traceable

- Security requirements are tied to services, not documents

- Acceptance criteria can be verified later without human interpretation

Cloudaware insight: Planning only holds if intent can be checked after deployment. Cloudaware helps teams establish service ownership and baselines early using CMDB relationships, so later stages can verify that runtime configurations and changes still match approved intent.

Phase 2. Code: secure development without slowing teams

This stage exists to ensure that security expectations defined during planning are reflected in how code is written and reviewed. Nothing is enforced blindly here. The goal is to prevent obvious violations from entering the pipeline and to preserve ownership as changes start to spread across repositories.

At this point, teams decide:

- which secure coding practices are mandatory

- which changes require additional review

- which dependencies are allowed by default

- Which teams own remediation when issues appear

Security at the code stage focuses on developer-controlled signals. Secrets, unsafe defaults, and high-risk dependencies are identified early, before they turn into build failures or release blockers. The intent is not to stop developers, but to reduce noise later in the pipeline.

What “done” means in the code phase

- Ownership remains clear as code moves across repositories.

- High-risk patterns are detected before build.

- Code-level decisions do not rely on manual interpretation later.

Cloudaware insight: Code-level findings become actionable only when they retain service and ownership context downstream. Cloudaware preserves this context through CMDB relationships, so issues discovered later in build or runtime can still be traced back to the correct service and team instead of turning into generic findings.

Phase 3. Build: CI as the first hard security gate

The build phase is where security decisions become enforceable. Once a change reaches CI, outcomes must be deterministic. A build either produces an artifact that meets policy or it fails. This is the first point in the lifecycle where automation replaces judgment.

At this stage, teams decide:

- Which checks are mandatory for every build

- Which failures block artifact creation

- Which results must be retained as evidence

- Which artifacts are allowed to move forward

The build phase has two separate control layers, both of which must pass before an artifact can be trusted.

Build-time security testing and SBOM generation

Build-time checks validate what can be assessed reliably, such as static analysis, dependency risk, and configuration rules. An SBOM generated here locks in a precise view of what the artifact contains, so later findings can be traced to a specific build instead of triggering broad rework.

Supply chain controls and artifact integrity

Artifacts are scanned, signed, and stored in controlled registries. Integrity controls ensure the artifact tested is the artifact released. Without this, release approvals lose their meaning.

What “done” means in the build phase

- Required checks run automatically and block on failure.

- Only compliant artifacts are created.

- Build outcomes are auditable later.

Cloudaware insight: Cloudaware supports this stage by maintaining an auditable record of build-related changes and policy evaluations. This allows teams to demonstrate which controls applied to which artifacts without reconstructing CI history after the fact.

Phase 4. Test: security testing that proves real risk

This stage exists to validate whether a change is safe to release, not to generate findings. The test phase answers one question only: does this version introduce risk that should block promotion. Anything that cannot influence that decision does not belong here.

At this point, teams decide:

- Which security failures block a release

- Which results are advisory only

- Which environments produce release-grade signals

- Who can override a failed test and why

Security testing is treated as a single decision surface. Dynamic testing, API testing, interactive analysis, and fuzzing are all inputs to the same outcome. The tool choice matters less than whether the result changes the release decision. Tests that do not feed a gate quickly turn into background noise.

What “done” means in the test phase

- Test results are tied to a specific release candidate

- Blocking conditions are explicit and enforced consistently

- Overrides are intentional and recorded

Cloudaware insight: Cloudaware helps teams retain test results as part of the release record by linking them to services, environments, and approved changes. This makes it clear which risks were evaluated and accepted at release time, instead of reconstructing that context later during incidents or audits.

Phase 5. Release and deploy: controlled change, not manual approvals

This stage exists to control how approved artifacts move into environments. Release and deploy are not about re-testing security. They are about enforcing intent when risk changes. If promotion rules are unclear here, teams fall back to ad hoc approvals that slow delivery and leave weak audit trails.

At this point, teams decide:

- Which changes require explicit approval

- Which environments have stricter promotion rules

- Which risks can be accepted automatically

- Who is allowed to override a gate

Release decisions must be consistent and repeatable. An approval should represent a recorded policy decision tied to context, not a chat message or a checkbox added at the last minute.

Policy-as-code approvals and release gates

Approvals work only when they are driven by policy. Gates evaluate the artifact, the target environment, and the current risk posture, then produce a clear outcome: allow, block, or require approval. This keeps releases predictable and prevents approvals from becoming informal bottlenecks.

What “done” means in the release and deploy phase

- Promotion rules are explicit and enforced automatically

- Approvals are tied to policy and context

- Release decisions are traceable later

Cloudaware insight: Cloudaware supports controlled releases by tying approvals and policy decisions to configuration state and change history. This allows teams to show why a deployment was allowed at that moment, based on the conditions that existed at release time.

Phase 6. Operate: DevSecOps infrastructure and runtime security

This stage exists to verify that what is running still matches what was approved. Once software is deployed, assumptions made earlier begin to decay through configuration changes, platform updates, and operational fixes. The operate phase is where security moves from expectation to observation.

At this point, teams decide:

- Which infrastructure and platform controls must always hold

- Which changes are acceptable without re-approval

- Which conditions trigger investigation or rollback

- Who owns runtime decisions

DevSecOps infrastructure covers identity, networking, compute, storage, and orchestration layers. Controls here are not preventative. They are corrective and detective, focused on detecting deviation rather than blocking change.

Cloud and platform controls in running environments

Runtime controls observe how systems are configured and used. Identity policies, network exposure, and platform settings are checked against approved baselines to surface unexpected change.

Continuous verification and configuration drift

Drift detection ensures that configuration changes are visible and evaluated. When drift appears, the question is not who changed what, but whether the change is acceptable under current policy.

What “done” means in the operate phase

- Runtime state matches approved intent or deviations are explained

- Drift is detected and recorded

- Ownership for runtime decisions is clear

Cloudaware insight: Cloudaware continuously compares live configurations to approved baselines and records configuration drift across cloud and platform layers. This allows teams to verify runtime reality against intent without relying on manual checks or periodic reviews.

Phase 7. Monitor and feedback: closing the DevSecOps lifecycle

This stage exists to ensure that incidents and findings change future behavior. Monitoring is not an endpoint. It is the mechanism that feeds lessons back into planning, code, build, and release so the same failures do not repeat under a new name.

At this point, teams decide:

- Which runtime events require action

- Which findings change future gates or policies

- Which fixes are permanent versus situational

- How quickly controls must adapt

Incidents expose gaps between intent and reality. Fixes close the immediate issue. Controls are updated so the next change is evaluated differently. This loop is what turns the DevSecOps life cycle into a system that improves over time instead of accumulating exceptions.

What “done” means in the monitor and feedback phase

- Incidents result in concrete control changes

- Policies and gates evolve based on observed risk

- Feedback reaches earlier stages without manual handoff

Cloudaware insight: Cloudaware supports this feedback loop by retaining change history, drift events, and compliance evidence over time. This allows teams to trace incidents back to prior decisions and update policies and baselines so future changes are evaluated with the same context.

Read also: DevSecOps vs CI/CD: How to Build a Secure CI/CD Pipeline

Roles, ownership, and responsibility across the DevSecOps lifecycle

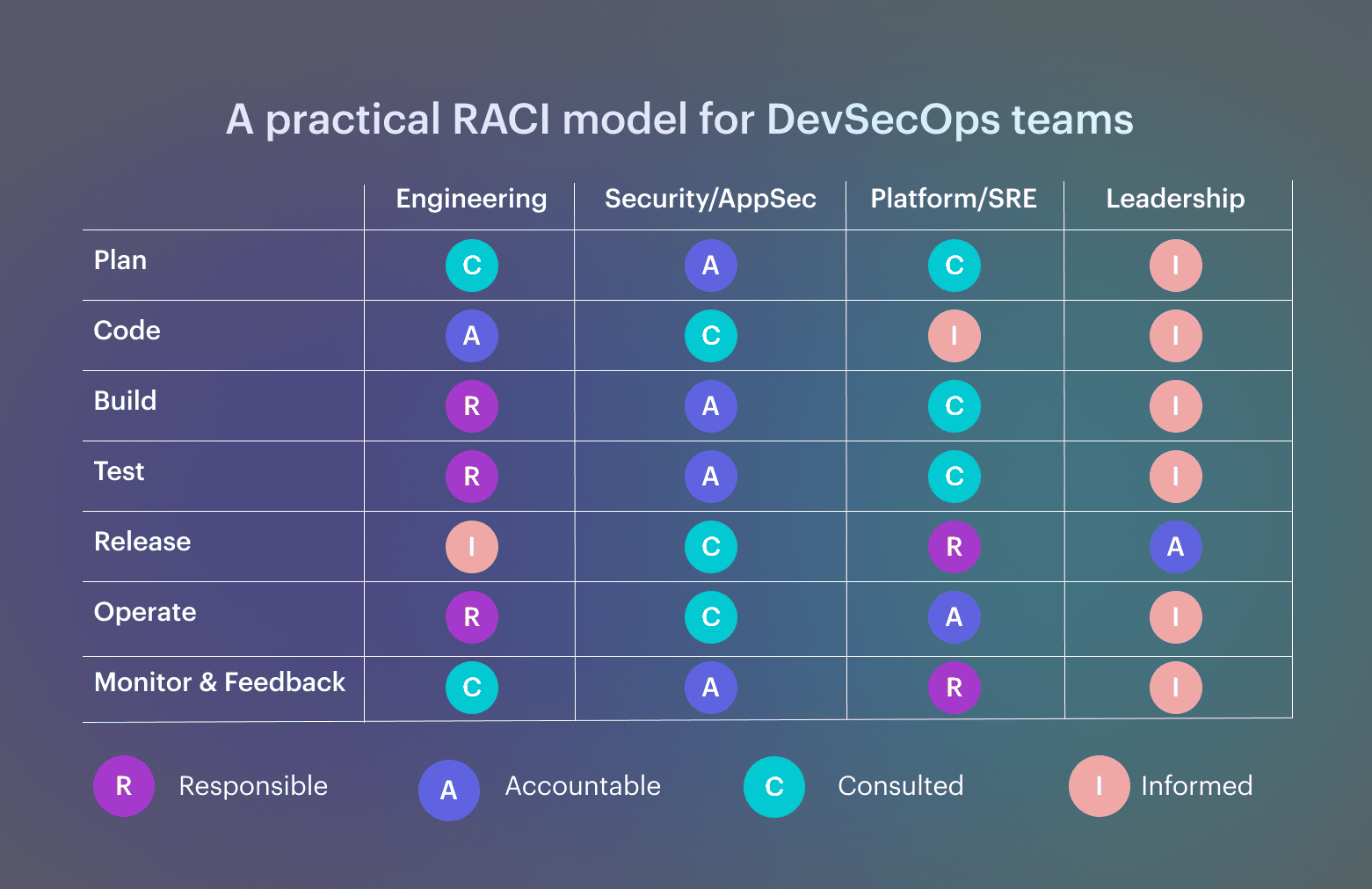

What teams need is not shared responsibility, but clear decision boundaries. Each stage in the lifecycle introduces moments where something can be allowed, blocked, or escalated. Someone must own that call, and that ownership must remain stable even as teams and systems change. This section clarifies the DevSecOps role across the software development lifecycle:

Who owns decisions at each stage

- Plan: architecture and security define constraints; engineering commits to scope

- Code and build: engineering owns fixes; security sets enforcement rules

- Test and release: platform enforces gates; leadership accepts residual risk

- Operate and monitor: platform owns runtime state; security updates controls

A practical RACI model for DevSecOps teams

A useful RACI assigns one accountable owner per decision, limits approvals to risk changes, and ensures outcomes are recorded. This is what keeps the DevSecOps lifecycle predictable instead of negotiable. Note: One accountable owner per decision. Approvals only where risk changes. Evidence recorded automatically.

Note: One accountable owner per decision. Approvals only where risk changes. Evidence recorded automatically.

Evidence and measurement: how DevSecOps proves it works

Evidence answers “what happened and why.” Metrics show whether controls improve delivery or quietly slow it down. Without both, DevSecOps becomes opinion instead of an operating model.

Evidence you should be able to produce at each stage

Teams should be able to show, on demand:

- Plan: approved scope, owners, and security requirements

- Code: policy violations detected before build

- Build: which checks ran, which failed, and which artifacts were created

- Test: release-blocking results tied to a specific candidate

- Release: why a deployment was allowed at that moment

- Operate: detected drift and how it was handled

- Monitor: which incidents changed future controls

If evidence cannot be reconstructed without manual work, the lifecycle is fragile

Metrics that show DevSecOps maturity

Not all metrics are equal. Output metrics (number of scans, findings, tools) say little about control quality. Mature DevSecOps programs rely on outcome metrics drawn from established frameworks.

In security programs aligned with CIS benchmarks, teams usually track:

- Configuration drift rate, to see how often runtime settings diverge from approved baselines

- Mean time to detect misconfiguration (MTTD), which shows how quickly drift is noticed

- Mean time to remediate misconfiguration (MTTR), which reflects how effective correction really is

These metrics indicate whether controls continue to hold after deployment, not just whether a release passed initial checks.

When FinOps practices are applied to DevSecOps, teams tend to measure:

- Change failure rate, including rollbacks caused by security or policy violations

- Cost of incidents and rework, as a practical signal of control quality

- Ratio of automated to manual approvals, which exposes how predictable and scalable the process is

Taken together, these metrics show whether the DevSecOps lifecycle produces stable outcomes, remains observable, and improves over time.