If you work with cloud environments, CI/CD pipelines, and security requirements, this question comes up sooner or later.

DevSecOps vs SDLC: are they the same concept, different approaches, or ideas that should not be compared at all?

The confusion is common. Some teams treat DevSecOps as a replacement for SDLC, while others view Secure SDLC as a prerequisite for any DevSecOps effort. And the confusion is often surfaces during audits, internal reviews, or board-level discussions, when teams are asked to explain what is actually in place.

The definition below addresses that confusion directly.

TL;DR

- SDLC defines the software development lifecycle, including what happens and in what order

- DevSecOps is an operating model that shapes how teams execute work and integrate security across all stages

- Secure SDLC defines mandatory security requirements within the SDLC

- Organizations typically combine DevSecOps and SDLC to address different operational and governance needs

Simply put, SDLC provides structure, Secure SDLC defines security expectations, and DevSecOps ensures those expectations are applied consistently as software changes.

Why DevSecOps and SDLC are often confused

DevSecOps and SDLC are often discussed in the same conversations, even though they address different problems. For platform and engineering teams, that overlap rarely stays theoretical and usually turns into operational friction.

One source of confusion comes from how leadership frames the topics. SDLC is usually discussed in terms of phases, checkpoints, documentation, and governance. DevSecOps enters the conversation around speed, automation, and coordination across teams.

Both discussions reference security and tooling, which makes them sound related, even when the expectations behind them are different.

Another factor is how delivery models have evolved. Many SDLC models were designed for slower release cycles and clear handoffs between teams. DevSecOps took shape later, driven by cloud platforms and continuous delivery, where work moves constantly and boundaries between build, release, and operations are less defined. The language around process did not evolve at the same pace as delivery practices.

Security adds a third layer to the overlap. Secure SDLC introduces required activities at defined lifecycle stages, while DevSecOps focuses on how security is executed as code and infrastructure change. When these perspectives are not clearly separated, requirements intended for governance are pushed into pipelines late, often as additional gates or checks that platform teams are asked to enforce without clear ownership.

This is why platform teams frequently inherit conflicting requests:

- CI/CD pipelines are expected to satisfy Secure SDLC controls, even when those controls were defined for lifecycle checkpoints rather than continuous execution

- Delivery speed expectations remain unchanged, so pipelines are also expected to support rapid releases and frequent changes

- Audit evidence is requested after the fact, which turns pipelines into reporting systems instead of delivery mechanisms

Without a shared understanding of what belongs to lifecycle structure versus execution, teams respond by adding tools, gates, and workarounds. These additions increase friction but rarely resolve the underlying issue.

Clarity comes from separating responsibilities. SDLC defines where controls are expected to exist, while DevSecOps defines how those controls are applied day to day. Until that distinction is explicit, confusion continues to surface as rework, duplicated tooling, and late-stage changes pushed into delivery pipelines.

The mental model: SDLC defines phases, DevSecOps defines execution

SDLC and DevSecOps solve different problems inside the same development process. SDLC controls how work is structured across the development lifecycle, while DevSecOps drives how that work is executed, automated, and secured as change moves through the system.

| Dimension | SDLC | DevSecOps |

|---|---|---|

| Primary role | Defines lifecycle phases | Drives execution across phases |

| Core focus | Order, sequencing, accountability | Flow, automation, coordination |

| Core questions | What happens and when? | How work runs continuously? |

| Scope | Development process structure | Operating model and collaboration |

| Change frequency | Planned and phase-driven | Continuous |

| Security ownership | Defined by role or phase | Shared across teams |

| Compliance and evidence | Collected at review points | Generated as changes occur |

This difference becomes visible when teams try to prove coverage, explain ownership, or respond to audit findings. SDLC identifies where controls are expected to exist within the lifecycle. DevSecOps determines how those controls are enforced as changes are introduced.

A common failure mode appears after deployment. A pipeline passes all required checks, release approvals are recorded, and the system goes live. Later, an IAM policy is modified, a network rule is relaxed, or a cloud resource is created outside the pipeline. The SDLC checkpoints were satisfied, but execution drifted. At that point, platform teams are asked to explain the risk, even though ownership and enforcement were never clearly defined.

Seen this way, SDLC provides fixed points for governance, while DevSecOps keeps security controls active as code, infrastructure, and configurations continue to change. The mental model only holds when both are understood as complementary, not interchangeable.

Read also: Understanding the DevSecOps Lifecycle in 2026

Where Secure SDLC fits into the picture

Secure SDLC defines concrete security requirements at specific points in the development lifecycle and makes those requirements part of how systems are designed, built, and reviewed. It works through checkpoints rather than continuous enforcement, which is why it aligns closely with governance and audit expectations. Problems tend to appear when Secure SDLC activities stop at documentation. Requirements are approved, threat models exist, but nobody can answer which cloud resources are in scope or who owns enforcement once systems are live.

Problems tend to appear when Secure SDLC activities stop at documentation. Requirements are approved, threat models exist, but nobody can answer which cloud resources are in scope or who owns enforcement once systems are live.

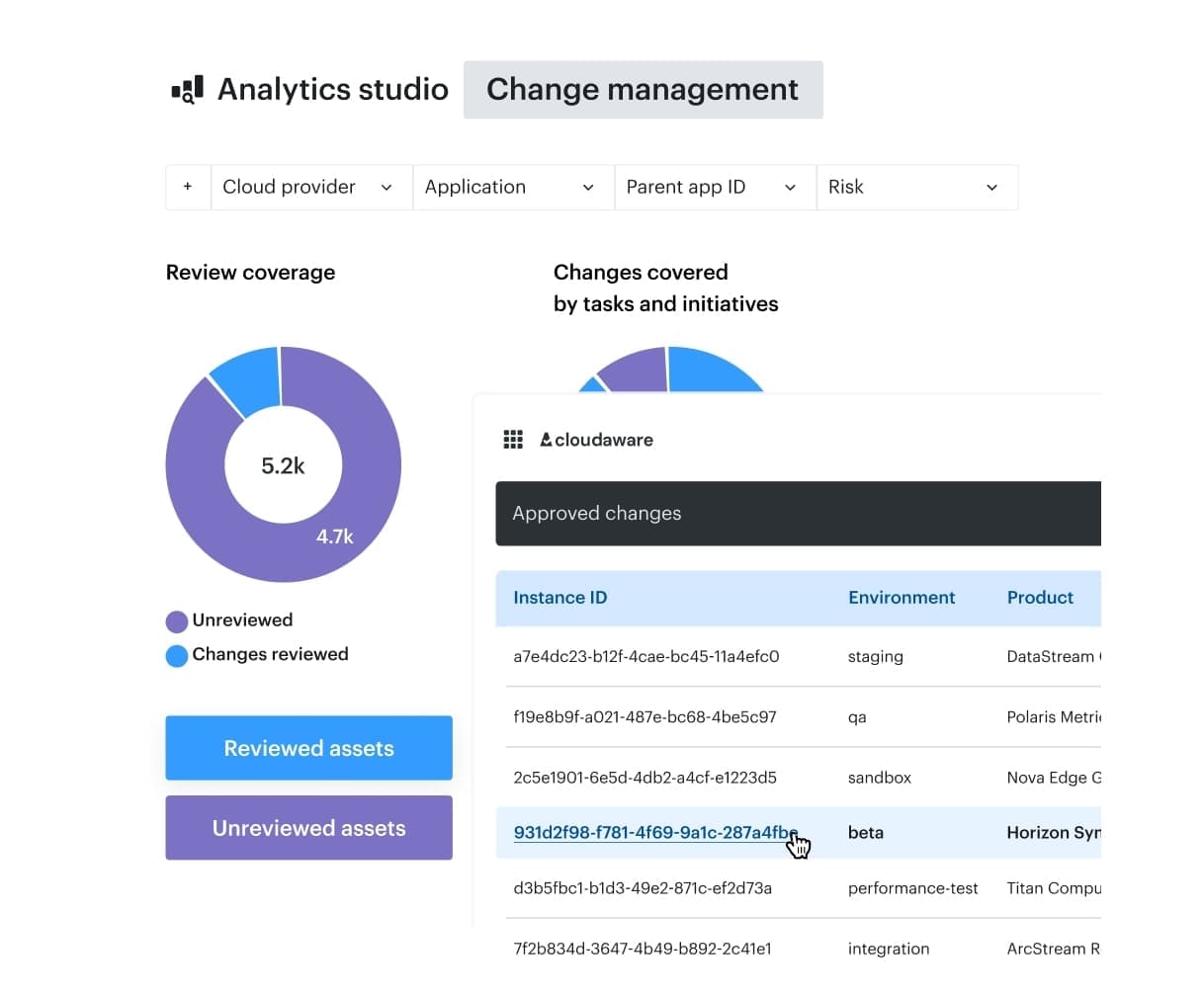

This is a common failure pattern we see before teams adopt Cloudaware. Once asset ownership and change history are visible across accounts and environments, Secure SDLC controls stop being abstract, while DevSecOps execution becomes enforceable because pipelines, policies, and audits reference the same inventory.

At that point, Secure SDLC defines what must exist, DevSecOps ensures it keeps running, and asset context prevents both from drifting as infrastructure changes.

Secure SDLC and industry frameworks (why enterprises care)

Enterprises rely on established frameworks to define expectations, demonstrate due diligence, and align security practices with external requirements. SSDLC is often anchored in these frameworks because they translate security principles into concrete guidance.

NIST Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF) focuses on what is required. It outlines core practices that organizations are expected to integrate into their development lifecycle, including governance, secure design, vulnerability management, and ongoing improvement.

Microsoft SDL focuses on how phases are structured. It defines specific security activities mapped to stages such as requirements, design, implementation, verification, and release, which makes it easier for teams to plan and enforce controls consistently.

OWASP SAMM focuses on how maturity is measured. It provides a model for assessing current practices, identifying gaps, and tracking progress over time across governance, design, implementation, verification, and operations.

What matters for most enterprises is not full framework adoption, but clear mapping. Auditors typically look for evidence that Secure SDLC requirements are defined, applied consistently, and traceable to recognized frameworks. Full SAMM maturity or exhaustive SDL implementation is rarely expected unless explicitly required by regulation or contract.

These frameworks explain why Secure SDLC is treated as a governance foundation rather than a collection of tools. They define expectations and structure, but they do not solve how evidence is collected, correlated, or maintained across real cloud environments as systems change.

Security activities across SDLC phases (with DevSecOps automation)

Security requirements only become effective when they are tied to concrete activities at each stage of the development lifecycle. Here SSDLC defines what must happen at each phase and DevSecOps determines how those activities are executed repeatedly as code and infrastructure change. Mapping both together makes it clear where execution lives and where evidence is produced. This mapping highlights why platform teams are frequently asked for logs, reports, and histories long after release. Evidence does not live in one place. Some artifacts originate in application workflows, while others are generated by cloud platforms and shared infrastructure after deployment.

This mapping highlights why platform teams are frequently asked for logs, reports, and histories long after release. Evidence does not live in one place. Some artifacts originate in application workflows, while others are generated by cloud platforms and shared infrastructure after deployment.

Secure SDLC establishes which activities must exist and which evidence is expected. DevSecOps ensures those activities run continuously. The model only works when teams can connect evidence back to real systems and clearly identify which platform or application component produced it.

Without that connection, evidence becomes fragmented across tools, ownership becomes unclear, and platform teams are left assembling proof after the fact rather than enforcing controls as part of normal delivery.

Which approach should you adopt first?

The right starting point depends on how software is delivered across your organization and how security outcomes are evaluated. In most enterprises, the answer is not uniform. Different teams, systems, and environments often require different approaches at the same time.

The checklist below helps identify where each model fits best 👇

Start with DevSecOps if most of these are true

- Software is released frequently, sometimes multiple times per day

- Teams rely heavily on CI/CD pipelines and cloud-native infrastructure

- Security findings must be addressed inside normal development workflows

- Ownership is distributed across engineering and platform teams

- Manual checkpoints slow delivery and are regularly bypassed

Trade-off: security expectations may remain implicit until they are later formalized.

Start with SSDLC if most of these are true

- Releases are gated and occur on a fixed schedule

- External audits or regulatory reviews drive security decisions

- Security requirements must be documented and approved by role or phase

- Evidence and formal sign-off are required before deployment

- Development teams operate within defined process boundaries

Trade-off: execution can become rigid as delivery speed increases.

Combine both approaches if most of these are true

- The organization spans multiple teams, platforms, and environments

- Some systems are highly regulated, while others change frequently

- Leadership needs execution visibility and formal assurance at the same time

- Security activities must be repeatable and auditable at scale

Trade-off: success depends on clear ownership and coordination across teams.

For platform teams, this mixed state is the norm. CI/CD-driven services, regulated workloads, and legacy systems usually coexist, and the same platform is expected to support all of them at once.

Most failures at this stage are not caused by missing process. They happen because teams lack a reliable view of what actually exists. When cloud assets, ownership, and scope are unclear, platform teams cannot tell which systems require SSDLC checkpoints, which should rely on continuous DevSecOps enforcement, and where exceptions apply. Decisions turn into assumptions, and enforcement becomes inconsistent. Platform teams need asset context rather than additional process. Cloudaware provides a view of cloud resources, ownership, and change history, so Secure SDLC controls and DevSecOps execution apply to real systems.

Platform teams need asset context rather than additional process. Cloudaware provides a view of cloud resources, ownership, and change history, so Secure SDLC controls and DevSecOps execution apply to real systems.

Common anti-patterns (and how mature teams avoid them)

Security programs tend to slow down in familiar ways once systems grow beyond a few teams or environments. The friction shows up where day-to-day execution stops lining up with ownership and where teams lose a dependable picture of what is actually running.

- Security at the end. Checks appear late, after releases are already planned and dependencies are fixed. Teams work around findings with exceptions or last-minute changes, and known risk moves forward because reversing course is too disruptive.

- Tools without gates. Scanners run and reports are generated, but deployments proceed the same way regardless of results. Findings accumulate in backlogs while delivery keeps moving.

- Alert fatigue with no routing. Signals arrive constantly, but nobody owns the queue. Platform teams see volume without context, application teams miss what applies to them, and serious issues blend into background noise.

- No ownership. Findings exist without a clear owner or timeline. Remediation stalls because responsibility never becomes concrete.

- No asset context. Reports exist, but teams cannot say which environments they represent or where gaps remain. Coverage is assumed instead of verified.

What good looks like

- Minimum controls. A small, explicit baseline applies everywhere, with clear rules for when exceptions are allowed.

- Automated enforcement. Controls run as part of normal delivery workflows, so enforcement does not depend on reminders or manual review.

- Continuous evidence. Evidence is generated as systems change, reducing the need for manual audit preparation.

- Clear ownership. Every asset, finding, and exception has an accountable owner, making remediation and decision-making predictable.

- Measurable response. Mature teams track how quickly ownership is assigned when a finding appears. A short mean time to ownership assignment is often a stronger maturity signal than scan coverage alone.

Teams that reach this stage usually address asset visibility early. Without a clear view of what exists, who owns it, and how it changes, even well-defined processes and strong tooling break down under real operational load.