“Does this actually block the release, or is it just another warning?”

That question shows up at the worst possible moment, after the pipeline has already finished and a security check has fired without context. Nobody remembers whether the rule is enforceable, who owns the decision, or what happened the last time this failed, so delivery slows while people reconstruct intent from logs and Slack threads. Not because security is strict, but because the system cannot tell the team what happens next if they don'thing.

In this article, you will learn:

- How real DevSecOps pipelines enforce decisions

- What each stage can block, and why

- How to spot gaps before they turn into release friction

What is DevSecOps pipeline in real terms

Most pipelines already look “secure” on paper. There are scanners in pull requests, checks in CI, and dashboards full of findings, yet when a release slows down, nobody can explain which result actually mattered or who made the call to move forward. That is usually when teams realize the pipeline is moving code, but it is not carrying decisions with it.

What is DevSecOps pipeline in real terms? A DevSecOps pipeline is an automated delivery flow that moves changes from code through deployment while applying security gates at each stage and producing artifacts and evidence that document the checks performed and the decisions made.

Read also: What Is DevSecOps - Definition, Security, and Methodology

DevSecOps pipeline diagram that shows control, not flow

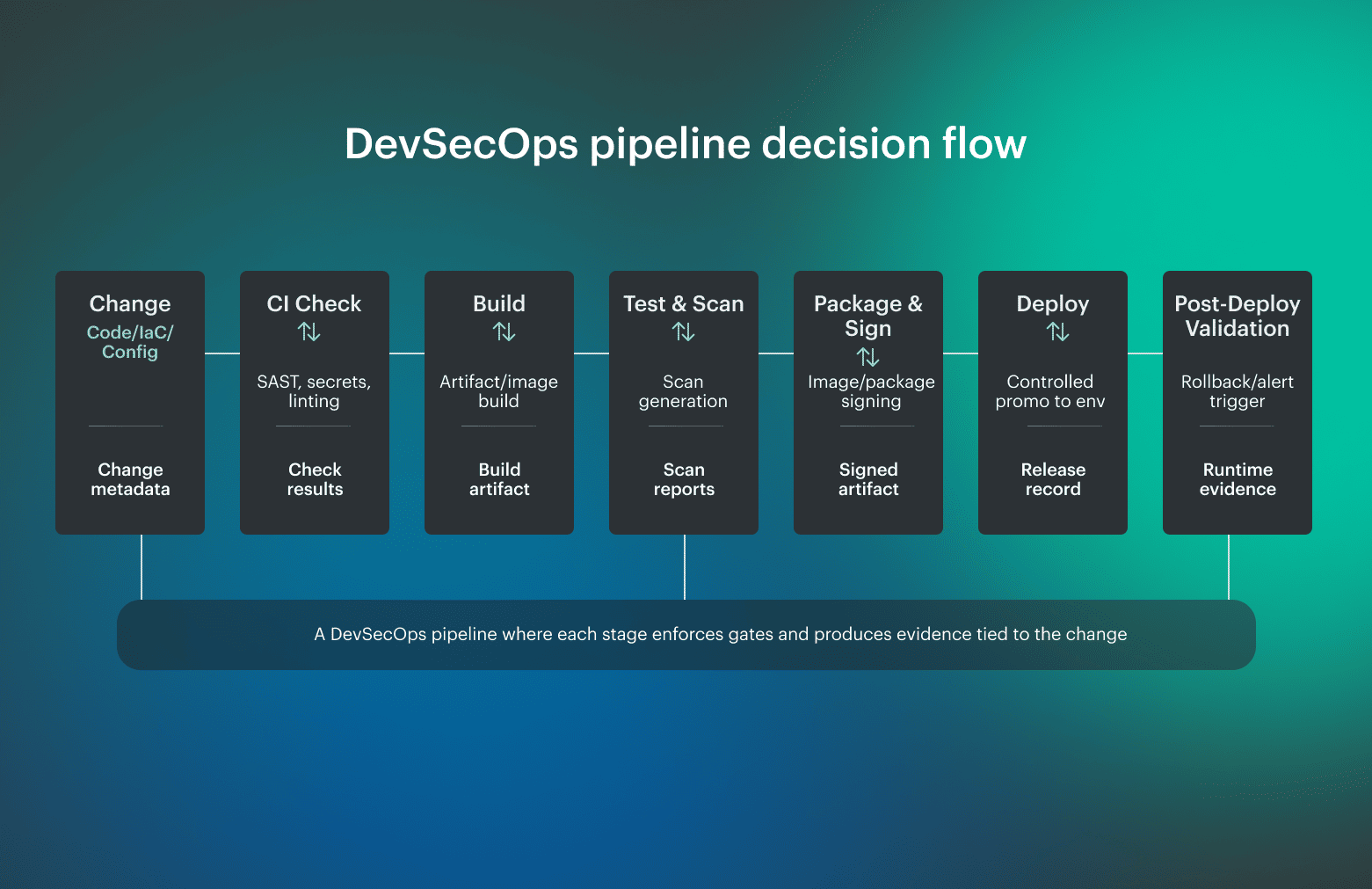

The visual below is the practical DevSecOps pipeline diagram image teams can screenshot and reuse as a reference flow.

Here, changes move from commit and pull request checks into build, test, scan, package, deploy, and post-deploy validation, but each transition is guarded by an explicit gate. Those gates decide whether an artifact can advance, and they do so based on defined thresholds rather than human memory. What matters just as much as the gates are the outputs. Each stage produces artifacts teams can point to later, including scan results, SBOMs, signed images, and a release-level evidence bundle that explains what was checked and why promotion was allowed.

What matters just as much as the gates are the outputs. Each stage produces artifacts teams can point to later, including scan results, SBOMs, signed images, and a release-level evidence bundle that explains what was checked and why promotion was allowed.

DevSecOps pipeline stages as decision boundaries

Most pipelines describe stages as a sequence of tasks, but that view hides the real risk. What matters is not just what runs, but what can stop promotion and what evidence survives once the stage is done. Thinking about stages in those terms makes it easier to spot where security is enforced and where it is only observed.

Why stages exist to answer questions and not to run tasks

The DevSecOps pipeline stages below reflect how pipelines behave in real environments, where checks repeat, thresholds matter, and artifacts created early are still needed long after deployment. This framing keeps the focus on decisions and outputs, not just activity, which is what makes a pipeline defensible when something eventually goes wrong.

This framing keeps the focus on decisions and outputs, not just activity, which is what makes a pipeline defensible when something eventually goes wrong.

Cloudaware insight: In practice, this breaks when stage outputs live in separate tools and logs. Some teams address this by introducing an asset and change context layer, where pipeline results, deployed resources, and runtime state are linked. Cloudaware is used to keep decisions, ownership, and evidence connected beyond a single pipeline run.

Read also: 10 DevSecOps Best Practices That Actually Survive Production

DevSecOps CI/CD pipeline architecture

Treat the DevSecOps CI CD pipeline as an architectural system made up of layers, each responsible for a specific kind of enforcement and evidence. When boundaries are explicit, teams can see where decisions are made and why a change was allowed to move forward.

Reference architecture layers:

- Source control and PR gates. This layer handles change intake and early enforcement

- CI runners and security scans. Builds, tests, and deeper security checks run in controlled CI environments

- Artifact, SBOM, and signing. Approved builds are stored with generated SBOMs and signatures

- Deployment, validation, and evidence storage. Artifacts are promoted into environments, validated against expected configuration, and recorded in an evidence store that ties runtime state back to the original change

For example, a Terraform change that weakens a storage policy may pass PR review but fail during CI scanning due to an IaC policy violation, stopping promotion until the policy is corrected and a clean, traceable artifact is produced.

Read also: Six pillars of DevSecOps - Practical Guide to Their Implementation in a Pipeline

DevSecOps pipeline architecture variations

A DevSecOps pipeline architecture changes as systems scale and constraints pile up, but the same questions keep resurfacing: where do gates belong, how much friction is acceptable, and what evidence needs to survive after release. The variations below show where teams usually feel that pressure first.

Mono-repo vs multi-repo

Mono-repo pipelines deal with wide blast radius. A small change can affect many components, which makes early, fast checks critical and pushes heavier validation later in the flow. Multi-repo setups reduce that coupling, but they depend on consistent pipeline rules across repositories to avoid uneven security enforcement.

Microservices at scale

Microservices increase release frequency and reduce change size, which shifts the problem from depth to volume. Pipelines must stay fast without letting security rules drift across dozens or hundreds of services owned by different teams.

Preview environments

Preview environments can surface issues early, but they become risky when teams rely on them as the only place security runs. If promotion rules are weaker upstream, findings often arrive too late to change outcomes.

Regulated workloads

Regulated systems require stricter separation of duties, stronger promotion controls, and longer evidence retention. Pipelines here are designed to explain decisions months later, not just to ship quickly today.

The two-speed pipeline model

Most mature teams settle on two speeds. Fast pipelines give rapid feedback on pull requests, while release pipelines enforce heavier gates and generate the evidence needed when delivery decisions are challenged later.

Read also: DevSecOps Architecture (A Practical Reference Model Teams Actually Use)

DevSecOps pipeline architecture diagrams teams actually use

As pipelines mature, DevSecOps pipeline architecture tends to reflect where risk actually lives. The two variants below show how teams visualize that in diagrams their teams actually use.

Variant A: cloud and IaC heavy

In cloud-centric environments, most risk enters through infrastructure changes. Pipelines here emphasize IaC validation, policy checks, and identity boundaries early in the flow, with promotion tightly controlled across accounts or subscriptions.

Evidence focuses on configuration state, policy decisions, and drift over time, because runtime reality is what auditors and incident reviews care about most.

Variant B: application and registry heavy

Application-focused systems push risk into build artifacts and images. Pipelines in this model center on dependency analysis, image scanning, signing, and controlled promotion through registries.

Evidence accumulates around artifact integrity, provenance, and versioned releases rather than environment configuration.

Both diagrams show the same architectural signals: where trust is established, where promotion is constrained, and where evidence is expected to persist.

Jenkins DevSecOps pipeline

Jenkins DevSecOps pipeline usually reflects lessons learned through operation rather than design. The patterns below show up repeatedly once pipelines have been running in production for a while.

- Stage placement matters more than tooling. Checks that run only once lose relevance as soon as the pipeline creates new artifacts

- Pipeline speed shapes behavior. As security jobs are added sequentially, feedback loops stretch and trust erodes

- Credential scope is a design choice, not a default. Jenkins does not enforce least privilege on its own. Treat it as a design decision: credentials must be short-lived and narrowly scoped per stage

This framing keeps Jenkins pipelines flexible without pretending they are safe by default, which is usually where teams get burned.

Read also: SecDevOps vs DevSecOps: Differences, Security Models, and When to Choose

DevSecOps pipeline GitHub

DevSecOps pipeline GitHub setup usually mirrors how teams already use pull requests and branches, which is why most effective designs align security decisions with workflow boundaries. GitHub’s own guidance and long-standing DevSecOps practice point to a simple rule: if a check is meant to block progress, it needs to run where ownership and intent are explicit.

Typical GitHub-based pipeline flow

- Pull request workflow. Fast checks run here to surface obvious risk before merge. Secrets scanning, lightweight static analysis, and basic policy checks give reviewers enough signal to make an informed decision

- Main branch workflow. This is where artifacts become real. Builds, deeper security scans, and SBOM generation run after merge, so results are tied to a stable commit

- Release workflow. Promotion is controlled at this stage. Artifacts are signed, approvals are enforced when required, and deployment decisions are recorded

This structure works because it matches how teams think about change and ownership, but it fails in predictable ways when checks are misplaced. In many cases, release workflows are skipped because promotion rules were never formalized, so checks run but don’t block or explain why a change was allowed.

Read also: DevSecOps Framework in 2026 - NIST, OWASP, SLSA, and How to Choose the Right One

GitLab DevSecOps pipeline

GitLab DevSecOps pipeline is shaped by merge requests and pipeline templates, which gives teams strong primitives for enforcing security if they use them deliberately. GitLab’s own documentation and long-running community practice emphasize that merge request pipelines are where intent is clearest, and that is where security checks carry the most weight.

Typical GitLab-based pipeline flow

- Merge request gates. Fast, blocking checks run as part of the MR pipeline so reviewers see security impact before approving a change

- Reusable templates. Shared pipeline templates define where security jobs run and how they are configured

- Fast feedback jobs. Lightweight security jobs run early to surface obvious issues, while heavier scans are deferred until artifacts exist

This structure works because GitLab enforces security directly through merge request pipelines and shared CI templates.

Read also: DevSecOps vs DevOps [Explained by a Pro]

DevOps CI/CD Azure pipeline for DevSecOps

DevSecOps Azure DevOps pipeline usually reflects enterprise constraints more than developer preferences. Azure enforces DevSecOps pipelines through multi-stage YAML definitions and explicit environment boundaries, which makes promotion decisions visible when teams keep stages intact.

Typical Azure pipeline structure

- Multi-stage YAML pipelines. Security checks are distributed across stages, so early feedback stays fast and heavier validation runs only after artifacts exist

- Environment approvals. Approvals act as formal gates for promotion into sensitive environments. When used deliberately, they create a clear record of who approved what and why

- Secure variables and secrets. Credentials and sensitive configuration are scoped to stages and environments rather than shared globally

This structure works when stages, approvals, and secrets are treated as enforcement points, not paperwork.

Read also: How to Build a Secure DevSecOps Toolchain Without Alert Fatigue

AWS DevSecOps pipeline

AWS DevSecOps pipeline usually fails in places that have nothing to do with scanners. The hard problems are identity, promotion boundaries, and proving what actually ran in each account when something changes. If those are vague, security checks can look “green” while the organization still carries uncontrolled risk.

What AWS-specific pipelines need to make explicit

- IAM blast radius. Pipeline roles should be narrowly scoped to the stage and account they operate in, because broad permissions turn a pipeline mistake into an environment-wide incident

- Multi-account promotion. Promotion should move artifacts across accounts, not rebuild them in each environment. That pattern keeps artifacts trusted between accounts and ensures rollback logic still refers to the same signed build

- Drift evidence. Post-deploy validation matters more in AWS than most teams expect, because runtime configuration changes constantly through consoles, automation, and managed services

Read also: 6 Core DevSecOps Automation Stages Across CI/CD

Azure cloud boundaries in a DevSecOps pipeline

Azure DevSecOps pipeline is shaped less by tooling choices and more by how subscriptions and access boundaries are organized. When those boundaries are unclear, pipelines end up enforcing checks in one place while risk accumulates somewhere else, which only becomes visible after an incident or an audit.

What Azure-specific pipelines need to make explicit

- Subscriptions as promotion boundaries. Pipelines should promote artifacts and configurations across subscriptions instead of rebuilding them

- Management groups for policy scope. Management groups define where guardrails apply. Using them deliberately ensures that security and compliance policies stay consistent across subscriptions without being reimplemented in every pipeline

- RBAC and policy guardrails. Role assignments and policy enforcement work best when they limit what pipelines can change by default. Guardrails reduce reliance on manual review and help keep enforcement predictable as environments scale

This structure holds up when subscriptions, management groups, and access rules are treated as part of the delivery system.

10 DevSecOps pipeline security controls that survive incidents

Most incidents don't happen because security tools were missing. They happen because controls ran once, too early, or without the authority to stop promotion.

In the video “How to Create a DevSecOps CI/CD Pipeline” by DevOps Journey, the author highlights a pattern many teams only recognize after something breaks: security checks lose value when they run only once, because new artifacts, dependencies, and configurations appear at every stage of the pipeline.

Why controls fail when they run only once

That observation matches what shows up repeatedly in postmortems. Effective DevSecOps pipeline security depends less on the number of checks and more on whether controls repeat as artifacts change, enforce thresholds, and produce durable evidence.

The controls below are the ones that consistently prevent incidents rather than just documenting them:

- Secrets hard-fail when exposed, without informal exception paths

- Dependency exploit gating based on exploitability, not raw CVE counts

- IaC misconfiguration gates that block unsafe defaults before deployment

- Repeated static checks after build, when new artifacts exist

- Signed artifacts and provenance to prevent silent changes during promotion

- Least-privileged pipeline identities per stage and environment

- Drift detection for changes outside the pipeline

- Evidence per release that survives audits and incidents

- Runtime signals tied to releases, not floating alerts

- Rollback triggers defined before something breaks

Read also: 13 DevSecOps Metrics for 2026 - What to Measure and Why

Why adding scanners rarely fixes DevSecOps pipelines

Most DevSecOps rollouts don't fail loudly. They fade. Pipelines keep running, scans keep producing output, and over time, teams stop treating the results as signals that require action. By the time an incident forces attention back to security, the controls are technically present but operationally irrelevant.

- Alerts without policy. Findings arrive without clear thresholds or consequences, so every result turns into a discussion instead of a decision. When nothing explicitly blocks promotion, teams learn that alerts are optional

- No ownership. Security findings land in shared inboxes or dashboards with no clear owner. Issues linger because nobody feels responsible for fixing them, and pipelines quietly move on

- Slow pipelines. Heavy scans run in the critical path without regard for feedback timing. As wait times grow, teams look for ways around the pipeline, which undermines enforcement even when checks are correct

- No post-deploy validation. Once code is released, security stops watching. Drift accumulates, runtime changes go untracked, and the pipeline loses the ability to explain whether production still matches approved intent

Read also: DevSecOps Roles and Responsibilities - Who Does What and Teams Structure

A DevSecOps pipeline self-audit you can run in minutes

If you can’t answer “what changed, when, and why” in 2 minutes, then the loop isn’t closed.

Use this checklist to see where your pipeline enforces decisions and where it only records activity:

- Can a failed security check actually block promotion, or does it just log a result?

- Do fast checks run before merge so reviewers see risk while intent is still clear?

- Are heavier scans tied to built artifacts, not branches that keep moving?

- Do static and dependency checks repeat after build, when new artifacts exist?

- Is every promoted artifact signed and traceable to a specific commit?

- Do you generate and store an SBOM per build, not per repo?

- Are severity thresholds defined so teams know what fails vs warns?

- Is ownership clear for fixing findings at each stage?

- Do pipeline roles follow least privilege per stage and environment?

- Does promotion move artifacts across environments, not rebuild them?

- Is there post-deploy validation to detect drift and unexpected changes?

- Are runtime signals linked back to a release, not floating alerts?

- Do you keep evidence per release long enough to survive audits?

- Are rollback conditions defined before incidents happen?

If several of these answers are “it depends” or “we think so,” the pipeline is running, but it isn’t enforcing.