DevSecOps is a delivery model where security controls run at the same enforcement points as build, test, and deploy decisions. When someone searches “What is DevSecOps?,” they usually expect a role or a toolset, but in real environments, it behaves like an operating model. Different orgs use the label for different mixes of application security, cloud security, and pipeline enforcement, and the boundaries shift depending on scale, regulation, and how delivery is actually run.

If you try to answer “DevSecOps what is” honestly, it comes down to making security part of the delivery flow. This guide keeps each topic short and links out to deeper articles when you need implementation details.

- DevSecOps definition and meaning

- What DevSecOps stands for, and why the name reflects shared ownership

- DevSecOps methodology: what to automate, what must stay a decision

- A DevSecOps workflow mapped to CI/CD

- How IaC and CSPM fit into DevSecOps

- Which roles own approvals, exceptions, and audit evidence

DevSecOps definition and meaning

Most teams can recite a definition, but the first time a release is blocked, the real question becomes, “Who owns this decision, and what happens next?” That is where DevSecOps either works or turns into a backlog of waived findings and forgotten exceptions.

When people ask “What does DevSecOps mean?” they are usually trying to separate “we added security tooling” from “we made security a predictable part of delivery.”

DevSecOps defined in plain English

DevSecOps is a delivery model where security controls run at the same enforcement points as build, test, and deploy decisions. In practice, it often looks like the overlap of application security and cloud security applied to the delivery path: the work ranges from SAST/SCA/DAST and security monitoring to cloud posture signals, incident response, and security architecture, with the exact mix varying by company size and how “DevOps” is defined internally.

In practice, it often looks like the overlap of application security and cloud security applied to the delivery path: the work ranges from SAST/SCA/DAST and security monitoring to cloud posture signals, incident response, and security architecture, with the exact mix varying by company size and how “DevOps” is defined internally.

That’s why folks often see conflicting expectations, because the label gets reused for different org shapes and different responsibilities.

Meaning behind the Dev-Sec-Ops name

DevSecOps means security is integrated into how work moves from change to production, not appended as a final checkpoint. The placement of “Sec” in the middle is a reminder that security needs to travel with the change through build and promotion, because that is where most exceptions are created, and most evidence is lost.

DevSecOps, defined this way, is less about ideology and more about where enforcement lives.

Definition of DevSecOps across the SDLC

A usable definition holds across the SDLC because risk shows up in different places as code becomes an artifact, then a deployment, then a running service.

Early checks catch obvious issues, but the common failures come from unclear ownership, inconsistent gates between environments, and exceptions that never expire.

DevSecOps fundamentals are stable enforcement points, explicit ownership boundaries per service and environment, and evidence that stays attached to the change so audits do not start with archaeology.

Shared responsibility explained

Shared responsibility does not mean everyone owns everything. It means ownership boundaries are explicit, and decisions have a home:

- Product teams own fixing issues in their services and dependencies

- Platform teams own enforcement points, pipelines, and promotion guardrails

- Security teams own policy intent, thresholds, and waiver conditions

- Release owners own go or no-go decisions when risk is accepted

- Auditors get evidence from the system, not reconstructed narratives

This DevSecOps approach reduces bottlenecks because decisions are made in-system, with escalation paths when a release needs an exception.

Read also: DevSecOps Statistics (2026): Market, Adoption, and AI Trends

Purpose and goals of DevSecOps

The question “What is the purpose of DevSecOps?” is usually asked after a team has tried to move faster and ended up moving risk instead. DevOps can optimize flow, but it does not define how security decisions are enforced, who owns exceptions, or how evidence is preserved when the pipeline and the organization change.

DevSecOps exists to make security outcomes predictable inside delivery, so controls do not depend on heroics at the worst moment.

Why DevSecOps exists

Security used to sit with a separate function at the end of the release path, and that model only “worked” when shipping happened in long cycles, and the backlog could absorb late findings.

Once delivery moved to weeks or days, the same late-stage security review stopped being a safety net and became a release throttle. Usually, such issues discovered after integration are more expensive to fix and harder to scope under pressure.

DevOps improved speed and feedback loops, but it did not automatically make security decisions enforceable inside the delivery system. DevSecOps exists to pull those decisions forward and make them repeatable end-to-end.

Read also: Six pillars of DevSecOps - Practical Guide to Their Implementation in a Pipeline

What outcomes DevSecOps teams aim for

The goals are operational:

- Fewer late surprises that derail releases

- Faster remediation because findings are tied to the change that introduced them

- Less exception chaos because waivers have owners and expiry

Teams also aim for cleaner audits because evidence is collected continuously, and for calmer incident reviews because the system can explain why a risky change shipped and what guardrails were bypassed.

Read also: DevSecOps Architecture: A Practical Reference Model Teams Actually Use

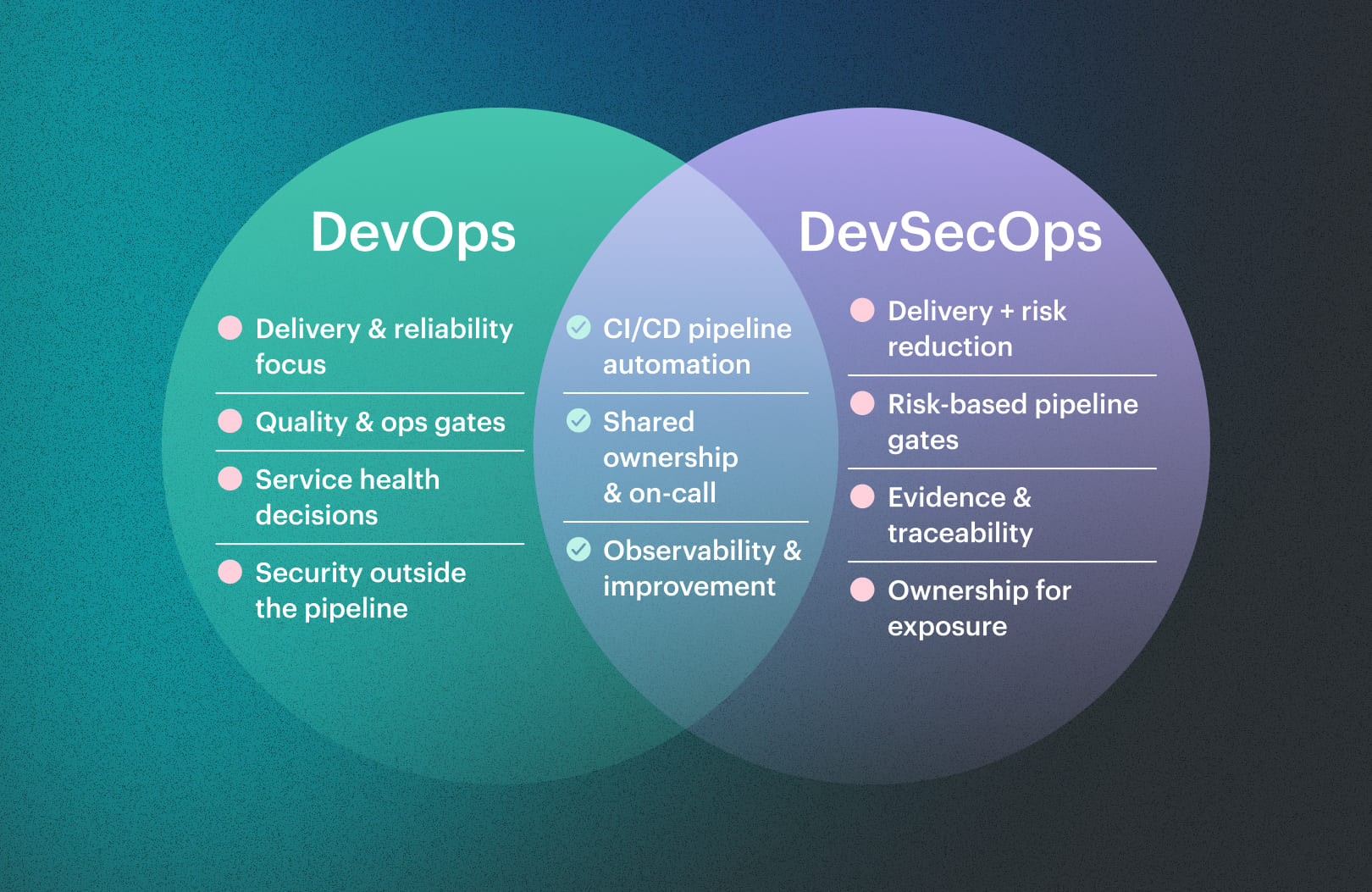

DevSecOps vs DevOps: what actually changed

DevOps made delivery faster by tightening feedback loops and removing handoffs, but DevOps security often stayed informal: a scanner posts findings, someone “takes a look,” and the release moves on with no stable record of what was accepted.

Security in DevSecOps is different because it treats risk decisions like any other production control, with enforced gates, explicit owners, and evidence that survives the quarter and the reorg.

DevOps security vs DevSecOps

The common break in DevOps security is missing enforcement. If a policy can be bypassed by switching channels, rerunning a job, or approving a ticket that is not tied to the build, the control does not exist under pressure.

DevSecOps security works when the pipeline is the enforcement point, waivers are first-class objects with owners, and promotion rules are consistent across environments.

Read also: SecDevOps vs DevSecOps: Differences, Security Models, and When to Choose

What changes vs what stays the same

What changes is how decisions are made: risk is handled in the same system that ships software, not after the fact. You still build, test, and deploy the same way, but you stop relying on interpretation at release time and start relying on policies that produce predictable outcomes. What stays the same is engineering accountability: product owners still own what runs in production, platform owners still own the delivery system, and security owners still set the risk thresholds, but the decision trail becomes part of the workflow instead of a postmortem artifact.

What stays the same is engineering accountability: product owners still own what runs in production, platform owners still own the delivery system, and security owners still set the risk thresholds, but the decision trail becomes part of the workflow instead of a postmortem artifact.

Read also: DevSecOps vs DevOps. What’s the Difference [Explained by a Pro]

What is DevSecOps methodology and operating model

When people ask about methodology, they are usually looking for something they can run repeatedly, not a maturity diagram.

A usable DevSecOps methodology defines where controls run, who can approve exceptions, and what evidence is retained when a change moves from commit to production. The DevSecOps approach is less about adding steps and more about turning security decisions into deterministic outcomes inside the delivery system.

Shared responsibility model

The DevSecOps process fails when ownership is “everyone,” because nobody is obligated to close the loop after a waiver or an incident. Shared responsibility works when boundaries are explicit and tied to enforcement points:

- Service owners remediate findings and own accepted risk for their workloads

- Platform owners maintain pipelines, gates, and promotion rules across environments

- Security owners define policy intent, severity thresholds, and waiver criteria

- Release owners make time-bound go or no-go calls when risk is accepted

- Compliance owners consume evidence from the system, not screenshots\

Read also: DevSecOps vs Agile - How Agile DevSecOps Works Across the SDLC

Automation vs human decision points

Most DevSecOps methodologies try to “shift left,” but automation only helps when it produces consistent decisions, not more noise. Gate what is objective and repeatable, observe what is contextual, and require a human decision when the business is explicitly accepting risk.

The best shift left methodology for DevSecOps teams uses automation to reduce ambiguity at merge, build, and promotion. This keeps exception handling and risk acceptance auditable and time-bound.

Read also: 6 Core DevSecOps Automation Stages Across CI/CD

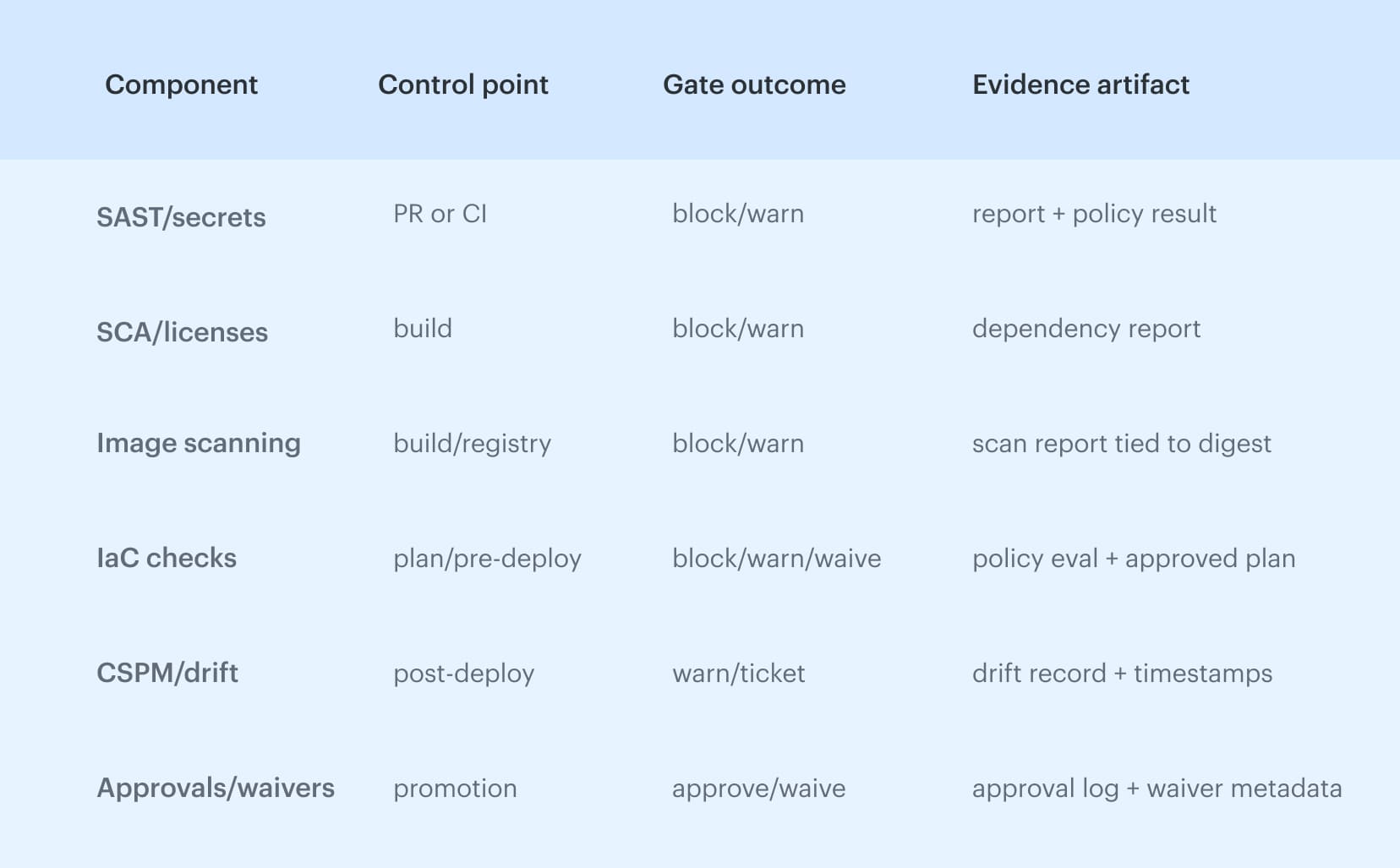

Key components of DevSecOps

The landscape is crowded, but most of it is optional once you map controls to real enforcement points. The components that matter are the ones that can stop or shape promotion, not the ones that generate another inbox feed.

If you need a quick answer to “What are the key components of DevSecOps?” think in terms of coverage across code, artifacts, infrastructure, runtime drift, and exception handling, with each control producing a decision and leaving evidence behind.

Core DevSecOps components

In practice, the stable set of components looks like this:

- Code controls: SAST and secret scanning at PR/CI

- Dependency controls: SCA and license checks during build

- Artifact controls: image/package scanning, signing, provenance

- Infrastructure controls: IaC validation and policy checks pre-deploy

- Runtime controls: CSPM posture and drift detection post-deploy

- Decision controls: approvals, waivers, and expiry-based exceptions

These are the DevSecOps capabilities that keep security decisions inside the delivery system. A plain list is not enough once you hit an audit request or an incident review, because you need to show where each control runs, what decision it can produce, and what evidence it leaves behind.

If a control cannot produce evidence later, it is not a control under audit, so the table below lays out the operational view of DevSecOps policy:

Read also: 10 DevSecOps Best Practices That Actually Survive Production

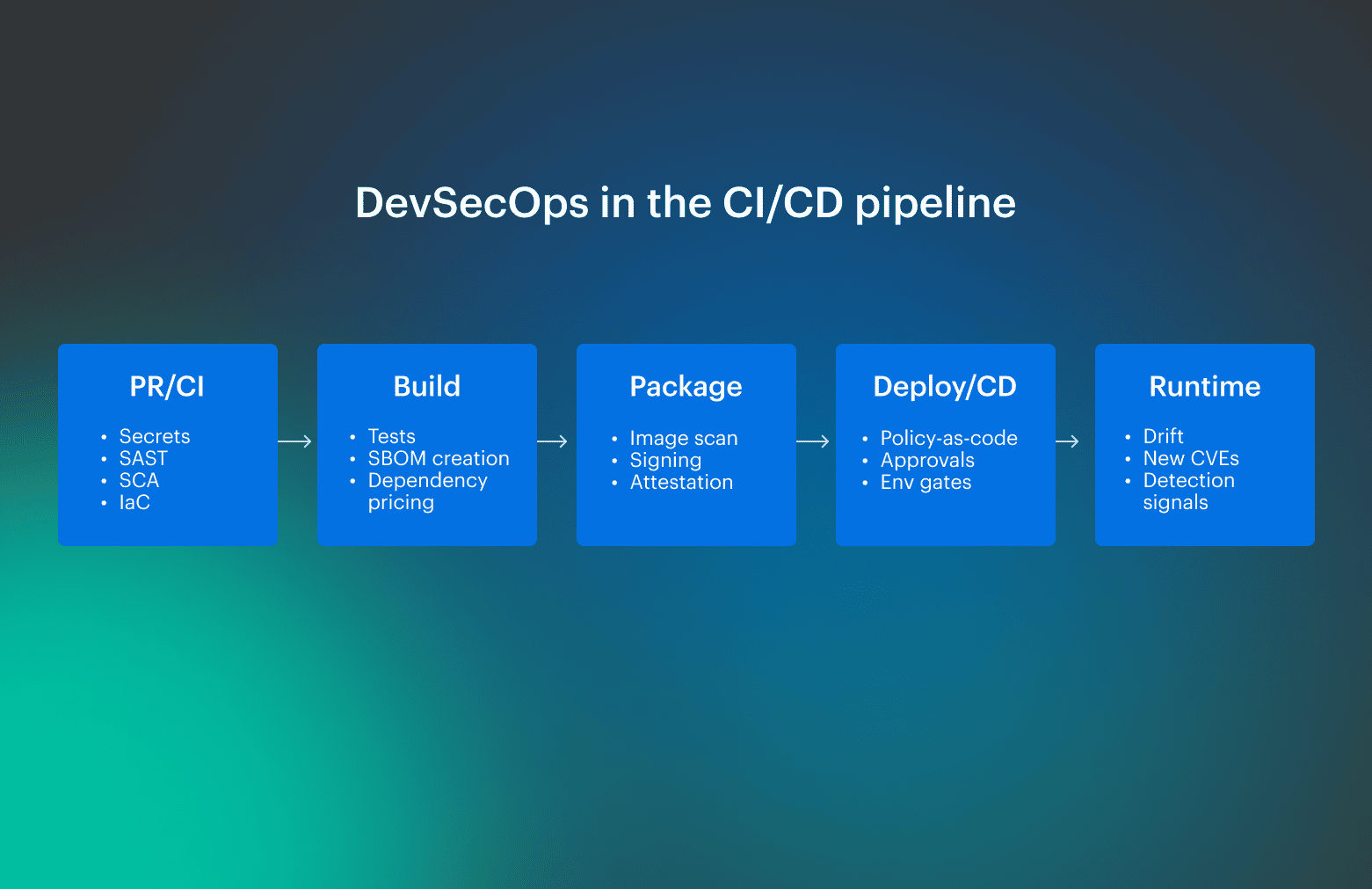

DevSecOps workflow and security gates across CI/CD

A DevSecOps workflow is only useful if it matches how changes actually move: merge, build, validate, promote, deploy, verify. The fragile version is “run scans somewhere in CI.” The workable version is a set of enforcement points with consistent outcomes, so promotion does not depend on who is online or how persuasive the request sounds.

DevSecOps vs CI/CD is where most misunderstandings start, because people treat CI as the whole model instead of the enforcement layer inside it.

DevSecOps continuous integration

In DevSecOps continuous integration lives in the same place as PR rules and CI checks. The goal is to get early, repeatable decisions that prevent known-bad changes from turning into expensive rollbacks later. Typical CI enforcement includes SAST, secret detection, dependency and license checks, unit tests, and policy thresholds that produce a deterministic block or warn outcome tied to the commit.

Typical CI enforcement includes SAST, secret detection, dependency and license checks, unit tests, and policy thresholds that produce a deterministic block or warn outcome tied to the commit.

DevSecOps integration and security gates

DevSecOps integration means the same policy intent is enforced across build, promotion, and deploy, with gates that map to risk and environment boundaries. A gate should do one job and do it predictably:

- Block when an objective threshold is violated (for example, critical policy breach)

- Warn when the signal needs triage, but should not stop delivery

- Observe when the control is informational, or the action happens after deploy

Read also: DevSecOps Pipeline Explained: Stages, Diagrams, and CI/CD Patterns

What is IaC in DevSecOps?

“What is IaC in DevSecOps?” comes down to where infrastructure risk is decided. Infrastructure-as-code is not just another artifact to scan; it is the change record that defines identity, network boundaries, and access paths before anything is deployed.

If infrastructure controls are advisory, the first real enforcement happens after the fact, usually during an incident or a surprise audit. Treat IaC as a control point, and the delivery system can prevent policy breaches before they become a running configuration.

IaC as a pre-deploy control point

IaC is the most direct way to express intent for a DevSecOps environment, because the plan describes what will change and where. Policy-as-code should evaluate that plan, not only the Terraform files, and it should return a decision tied to the proposed state.

Pre-deploy enforcement typically includes:

- Policy checks on identity and access changes

- Network boundary and exposure checks (public endpoints, ingress rules)

- Encryption, logging, and baseline configuration requirements

- Environment boundary rules (prod vs non-prod promotion constraints)

Handling exceptions without breaking delivery

Exceptions are unavoidable, but unmanaged exceptions become accidental drift. Treat waivers as time-bound approvals against a specific plan, with an owner and an expiry, then verify the deployed state against approved intent.

This keeps DevSecOps policy enforceable without turning every edge case into a manual review loop, and it separates approved drift from configuration changes that slipped in through side channels.

Role of CSPM in DevSecOps workflows

The role of CSPM in DevSecOps workflows is to keep cloud policy enforcement continuous, not episodic. Pipelines can gate what they can see at build time, but cloud risk also comes from inherited configuration, identity changes, and drift that appears after deployment.

CSPM closes that gap by verifying posture against policy intent across accounts and environments, and by feeding posture and drift signals back into delivery rules. That is the practical answer to “What is the role of CSPM in DevSecOps workflows?”: it keeps cloud controls alive between releases.

Pre-deploy: preventing policy breaches

Used pre-deploy, CSPM supports cloud security DevSecOps by validating that an intended change will not violate policy before promotion. This is most valuable when IaC is not the only path to production changes, or when multiple teams share accounts and guardrails.

- Catch policy violations before they ship (identity, network exposure, encryption)

- Enforce environment boundaries consistently (prod vs non-prod)

- Require an owner and a waiver when a policy must be broken temporarily

Post-deploy: drift detection and inherited risk

Used post-deploy, CSPM becomes an always-on verification loop. Drift and inherited risk are where “approved” releases quietly degrade, and where audits find gaps months later. This also strengthens DevSecOps observability because it turns posture into a measurable signal, not a periodic report.

- Detect drift from approved intent and track when it began

- Surface inherited misconfigurations that were not introduced by the latest release

- Preserve evidence over time so incident reviews and audits start with facts, not reconstruction

Read also: Inside the DevSecOps Lifecycle - Decisions, Gates, and Evidence

DevSecOps roles, challenges, and metrics

A rollout usually stalls for one reason: controls exist, but ownership does not. DevSecOps roles are less about titles and more about who can change gates, who can grant a waiver, and who carries a fix to closure when production pressure hits.

The other silent failure is measurement by activity; a DevSecOps dashboard that counts findings but can't show exception aging, drift, and bypass behavior will not survive audit questions.

DevSecOps engineer and team responsibilities

What is DevSecOps engineer work in practice? It is turning “be secure” into shipped defaults inside the paved road: pipeline templates, policy checks, hardened build patterns, and evidence emission that does not require humans to collect proof.

Responsibilities map to enforcement points:

- Maintain shared CI/CD guardrails and promotion rules

- Decide what blocks vs warns, and keep gates fast enough to stay enabled

- Normalize tool output so owners get one actionable signal

- Make waivers time-boxed, owned, and traceable to a change

- Partner with GRC on evidence that falls out of automation

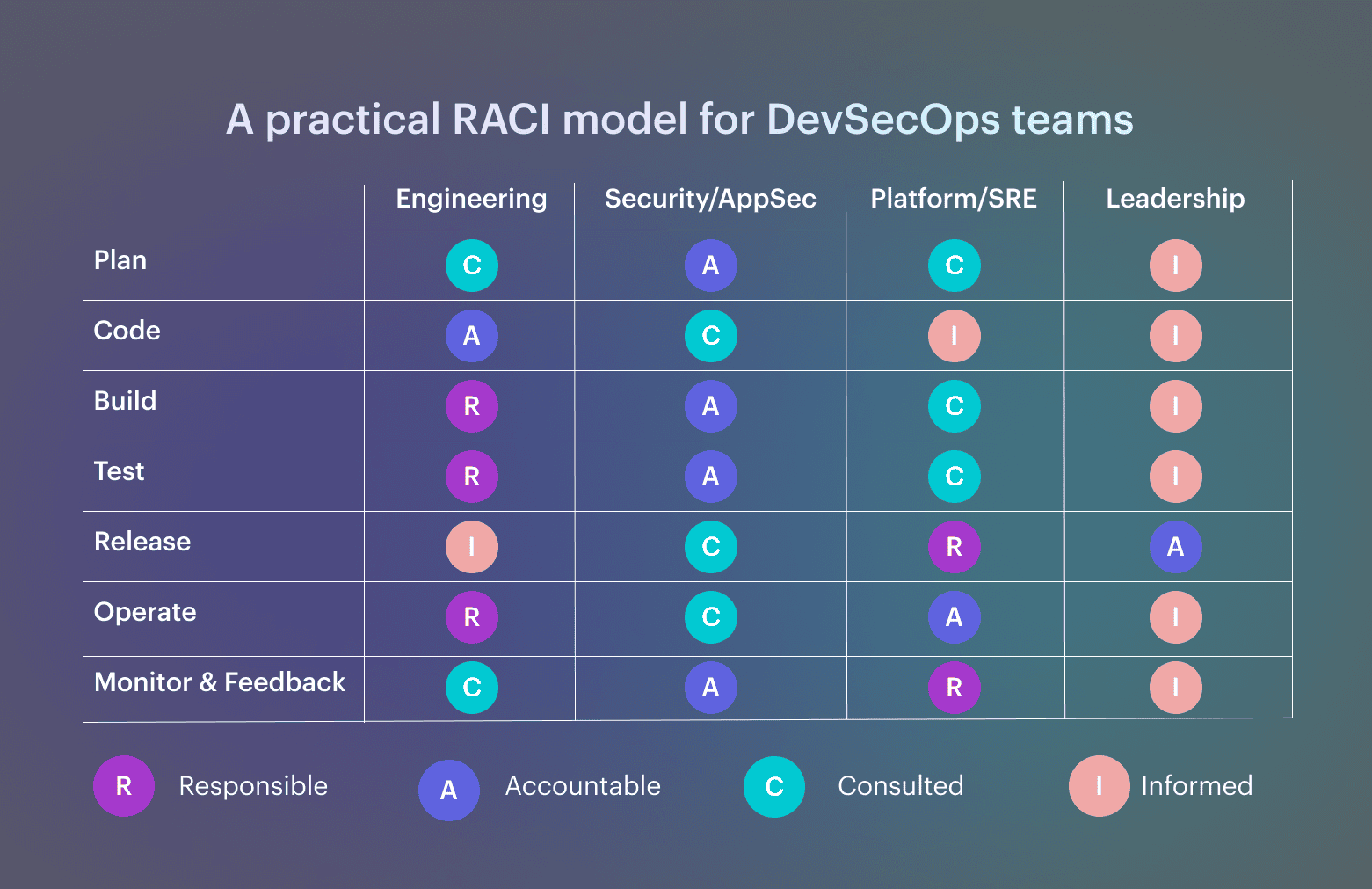

A pipeline does not care about an org chart; it cares about who is accountable when a gate blocks and who can approve a waiver without creating a side door. The RACI view below makes those decision owners explicit across delivery stages. RACI across plan, code, build, test, release, operate, and monitor stages.

RACI across plan, code, build, test, release, operate, and monitor stages.

Read also: DevSecOps Roles and Responsibilities: Who Does What and How Teams Are Structured

Common DevSecOps challenges and failure modes

Most DevSecOps challenges are predictable: tool sprawl that nobody tunes, ownership gaps that turn “shared responsibility” into approval roulette, and exception chaos where waivers never expire.

The dashboard should make those failures visible through DevSecOps metrics that correlate with delivery risk:

- Exception count and exception aging by service. This shows whether waivers are a controlled safety valve or a permanent side door. Aging is the real signal, because exceptions that outlive a release window usually become an invisible risk.

- Gate bypass attempts and manual deploy frequency. If engineers keep routing around gates, the control is either too slow, too noisy, or unclear in ownership. A rising bypass rate is an enforcement failure, not a “training” problem.

- Time-to-fix for high-severity issues tied to recent changes. This tells you whether the delivery system can absorb security work without stalling releases. When time-to-fix grows while deployment frequency stays high, the org is accumulating a risky backlog under pressure.

- Drift rate versus approved intent, and repeat policy violations. Drift separates “approved” from “actual” and exposes where changes are happening outside the intended path. Repeat violations usually mean the guardrail is missing or the default path is unsafe, not that people forgot the rule.

Cloud DevSecOps, observability, and standards

Cloud DevSecOps changes the failure modes. In the cloud, the risky move is often an identity permission, a public endpoint, or an inherited configuration that never went through a pull request. That is why cloud native DevSecOps relies on verified intent, environment boundaries, and continuous checks that detect drift after deployment.

This applies the same way across AWS, Azure, and GCP, and it becomes even sharper when the control plane is Kubernetes and “environment” means a mix of clusters, namespaces, and cloud accounts. If you treat security as a one-time pipeline step, DevSecOps in the cloud will degrade quietly between releases.

Cloud-native DevSecOps and observability

In a DevSecOps cloud environment, observability is not only logs and traces; it is visibility into policy breaches, drift, and exception behavior over time. The signals that matter are the ones that change release decisions or trigger rollback and remediation:

- Drift from approved intent, with timestamps and affected assets

- Identity changes that expand blast radius (roles, policies, trust relationships)

- Public exposure changes (ingress rules, endpoint configuration)

- Exception activity: waivers created, expiring, or repeatedly renewed

This is the practical side of DevSecOps observability because it links runtime state back to delivery decisions, whether the workload runs on AWS, Azure, GCP, or Kubernetes.

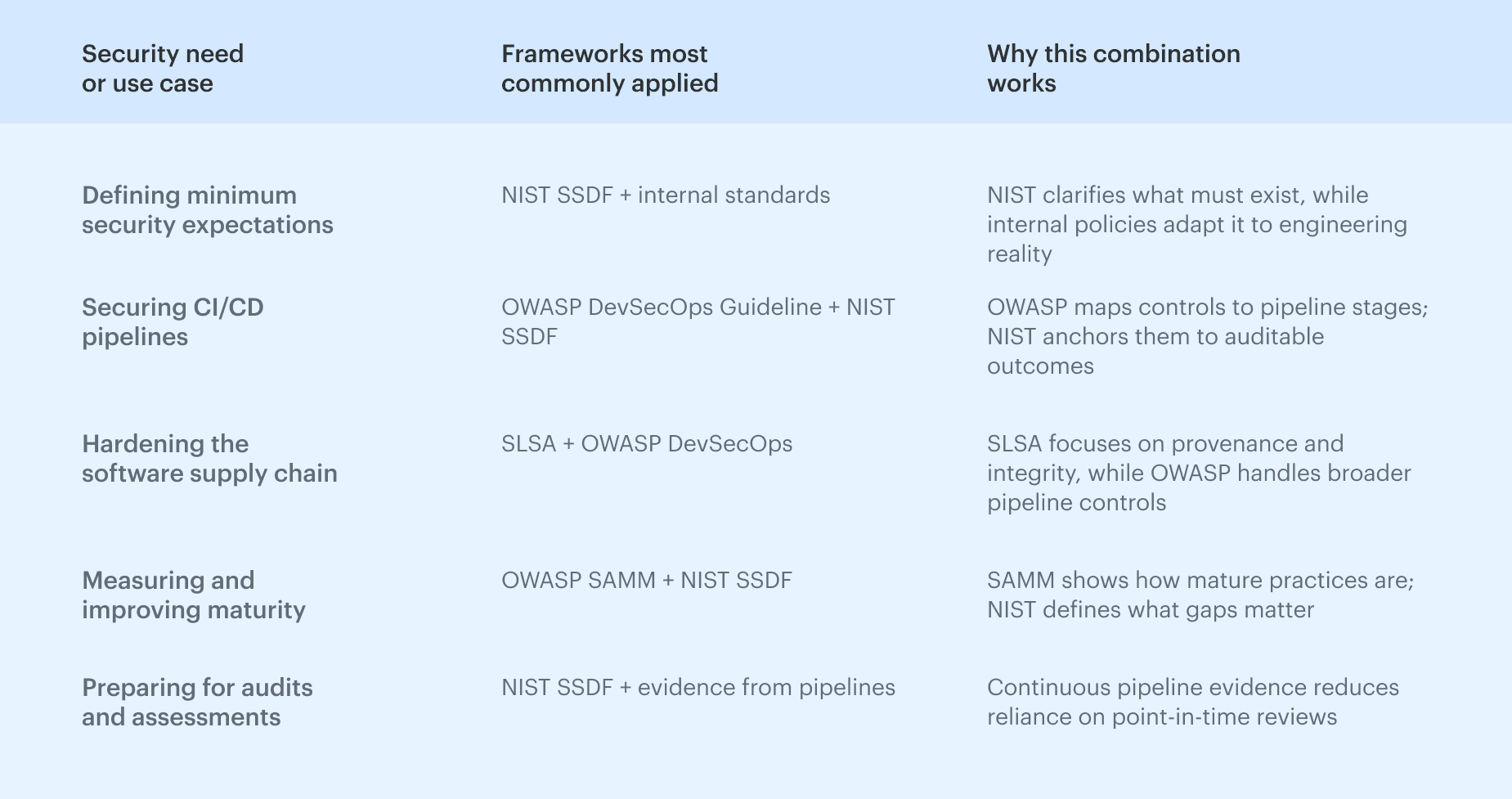

DevSecOps standards teams actually align with

DevSecOps standards are useful when they map to concrete controls and evidence, rather than becoming a documentation exercise.

Most orgs align to a small set of DevSecOps framework for different reasons: NIST for secure development practices, OWASP for application guidance, and SLSA for supply chain integrity, then they translate those requirements into gates, policies, and audit-ready artifacts. The point is consistency: the control must be enforceable in the delivery system and provable later without manual reconstruction.

The point is consistency: the control must be enforceable in the delivery system and provable later without manual reconstruction.