An ITIL CMDB is your system of record for configuration items—and the relationships that make them useful. Apps to services. Services to cloud resources. These resources are then allocated to their owners. That web is what turns “data” into decisions.

In ITIL 4, this information lives under Service Configuration Management. Not as a side quest. As the backbone that keeps service models, CI lifecycles, and dependencies reliable. When that backbone is strong, change doesn’t feel like roulette. Incidents stop being guesswork. Risk becomes something you can actually measure and explain.

Now, what does CMDB in ITIL look like when it’s real—trusted, current, and governed?

- Which ITIL practices depend on it most, and why?

- What’s the minimum data model you need to avoid a CMDB junk drawer?

- How do you keep discovery clean, ownership clear, and relationships accurate as environments shift?

- And when you evaluate CMDB tools, what features matter for hybrid cloud, not just demos?

Let’s walk it end to end.

What is an ITIL CMDB?

An ITIL CMDB is a living system of record for the things that make your services run—and the relationships that explain how they run. It tells you what exists, who owns it, what state it’s in, and what it supports. In practice, it’s how ITIL teams stop operating on guesswork and start operating on evidence.

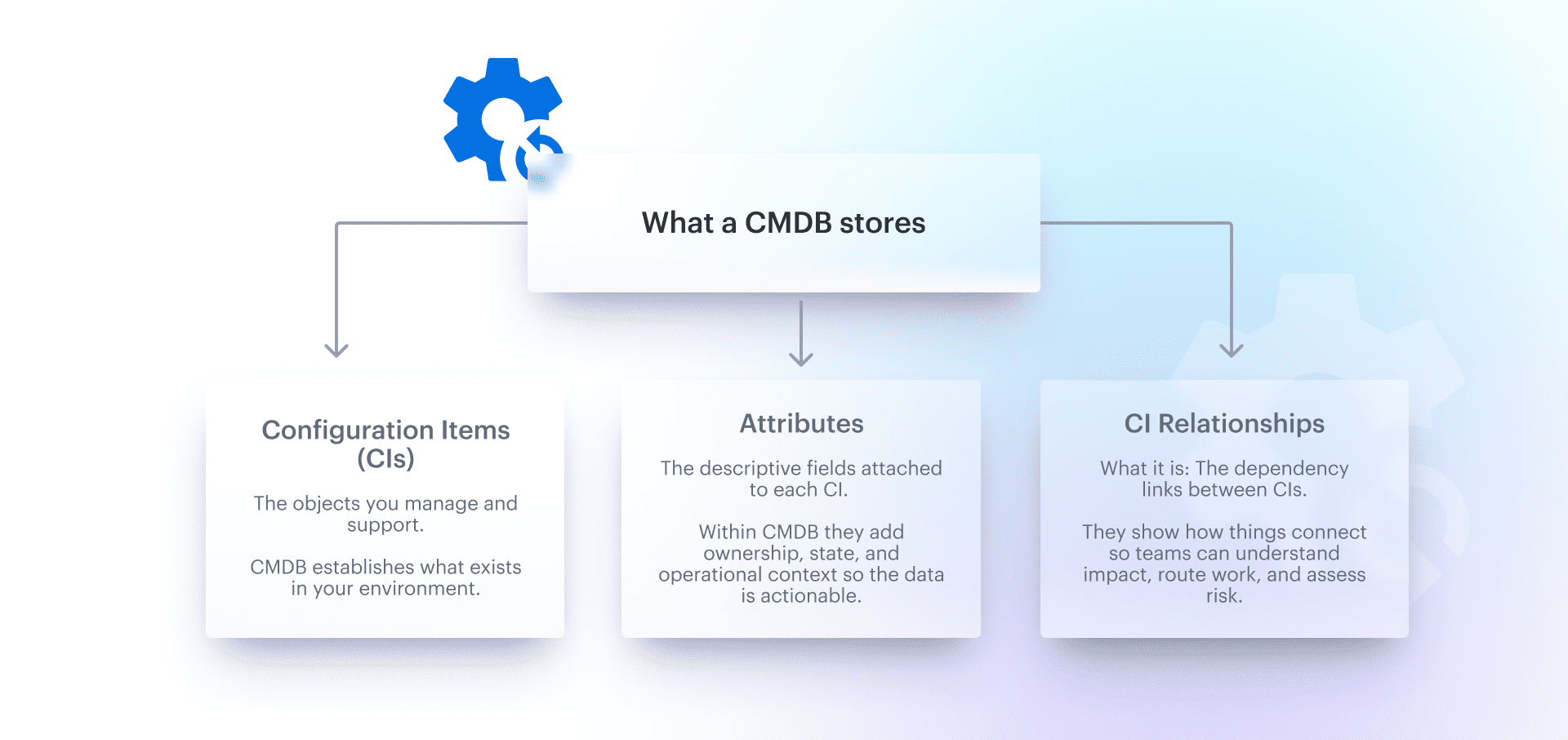

What a CMDB stores (CI types + attributes + relationships)

A useful CMDB ITIL tracks CIs, their attributes, and their relationships—and it treats each like a first-class citizen.

- CI types: business services, applications, microservices, VMs, containers, Kubernetes clusters, databases, load balancers, subnets, security groups, IAM roles, SaaS subscriptions, even on-prem gear if you still run it.

- Attributes: owner/team, environment (prod/dev), criticality, lifecycle state, region/account, compliance scope (PCI, HIPAA), patch level, tags like

CostCenter=FinOps,Service=Checkout,Tier=Tier-0. - Relationships: “Service A depends on App B,” “App B runs on EKS Cluster C,” “Cluster C uses Node Group D,” “Node Group D sits in VPC E,” “VPC E routes through NAT F,” “Logs go to Index G.”

That chain is how you get from “something is broken” to “here’s what’s actually impacted.”

Why CI relationships matter more than the list (impact, dependency, blast radius)?

A flat inventory can tell you what you have. It can’t tell you what matters right now.

Say a change request lands: “Rotate a TLS certificate on the load balancer.”

Cool. Which services are behind it? Which customer flows does it touch—login, checkout, onboarding? If your CMDB relationships are real, you don’t debate it in Slack. You run impact analysis and see the dependency tree.

Or an incident: an EKS node pool goes unhealthy in **eu-west-1**.

Without relationships, you page three teams and hope. With relationships, you instantly see which Tier-0 services run on that cluster, which databases they hit, and who owns the service. That’s smaller blast radius, faster routing, faster recovery.

That’s the whole point of ITIL CMDB: relationships turn ITIL processes—incident, change, problem, risk—from “best effort” into repeatable operations.

CMDB in ITIL 4: where it fits

It lives inside Service Configuration Management.

In ITIL 4, the CMDB isn’t its own practice. It sits inside Service Configuration Management (SCM). It is the discipline. And the CMDB is the system of record SCM relies on.

So when you ask “where does CMDB fit?” the answer is simple: it’s the data backbone that SCM maintains so other practices can make correct decisions.

Read also: What Is CMDB (Configuration Management Database)? Meaning, Examples & Benefits

What SCM uses the CMDB for (and what “good” looks like)

SCM is responsible for keeping configuration information trustworthy. That usually means the CMDB is managed with:

- CI scope rules: what’s a CI vs noise (services, apps, clusters, network, identity… not every transient object)

- Service models: mapping “business service → application → infrastructure dependencies”

- Lifecycle control: planned / active / retired, plus ownership and criticality

- Data quality controls: freshness SLAs, de-duplication, reconciliation, mandatory fields

For example, your “Checkout Service” isn’t a server. It’s a chain. SCM ensures the CMDB captures that chain and keeps it current—so you can see what supports Checkout and who owns each layer.

How CMDB “feeds” other ITIL practices

An ITIL CMDB doesn’t sit on the sidelines. It feeds the practices you run every day with the same thing they all depend on: trusted context. Ownership. Criticality. Lifecycle state. And—most importantly—relationships. When that data is current, change decisions get smarter, incidents route faster, problems stop repeating, and risk conversations shift from opinion to evidence.

Here are practical examples of ITIL workflows powered by CMDB

| ITIL 4 practice | How CMDB is used | Example output |

|---|---|---|

| Service Configuration Management | Defines CI scope, service models, lifecycle states, and data quality rules so configuration data stays trustworthy. | “Checkout Service” model showing supporting apps, infra, owners, and lifecycle status. |

| Change enablement | Uses CI relationships + criticality to run impact analysis and route risk-based approvals. | Change record with impacted services, owner approvals, planned window, and rollback steps. |

| Incident management | Maps alerts/affected components to services + ownership for fast routing and tighter incident scope. | Incident ticket pre-filled with impacted service, owning team, and related CIs. |

| Problem management | Links incident history to CIs to spot recurring patterns and isolate likely root causes. | Problem record showing repeated incidents tied to the same dependency chain. |

| IT asset management | Aligns inventory with ownership + lifecycle state to support decommission, renewal, and audit readiness. | Retirement candidate list filtered by “no service relationships + end-of-life.” |

| Information security management / risk | Adds scope + exposure context (internet-facing, regulated scope) tied to services and dependencies. | “PCI scope” asset/service list with public exposure flags and owners. |

What the CMDB contributes to change enablement

Change enablement is the ITIL 4 practice that controls change so you don’t trade speed for outages.

The job is simple to say and brutal to do: approve the right changes, block the risky ones, and do it fast.

That’s where CMDB ITIL stops being “documentation” and starts being decision support.

Change enablement needs two things that humans are terrible at holding in their heads:

- CI relationships: what depends on what (service → app → cluster → network → identity).

- Criticality: what matters most (Tier-0 vs non-critical, prod vs dev, revenue path vs internal tool).

Put those together and you get the real output: impact analysis. Not a meeting. A map.

How that turns into risk-based approvals

When relationships are trustworthy, you can approve changes based on risk, not confidence. You can answer, quickly:

- Which services are downstream of this CI?

- Is any of that production?

- Is any of that business-critical?

- Who owns the affected services?

Now approvals aren’t “yes/no.” They’re “yes, with controls.” Extra testing. Shorter window. Mandatory rollback plan. Owner sign-off.

One clear example

A change request comes in: “Update a security group rule for a shared ingress component.”

It sounds small. It always sounds small.

With CMDB relationships, you trace that ingress component to two customer-facing services. One is tagged as Tier-0 and runs in Prod. The other is lower criticality.

So the approval path changes:

- Tier-0 service owner gets pulled in.

- The window moves away from peak traffic.

- Rollback steps are required upfront.

- Monitoring is tightened for the first 30 minutes after deployment.

In Cloudaware, this is the moment where the CMDB earns its keep quietly: the CI record already carries environment and criticality fields, and the relationship chain shows which services sit behind that change. You’re not inventing risk from vibes. You’re reading it from context.

CMDB in ITIL incident management

Incident management in ITIL 4 is about one thing: restore service fast.

Not “find the villain.” Not “write the perfect timeline.” Restore.

And the thing that steals your minutes? It’s uncertainty.

An alert fires and everyone asks the same questions at the same time: What’s impacted? Who owns it? Is this real?

If you don’t have answers, the default behavior is predictable. You page broadly. You create a giant bridge. You burn half the org’s attention just to locate the actual problem.

This is where CMDB ITIL stops being “documentation” and becomes incident control.

A well-run CMDB gives you two anchors.

| First: service-to-CI mapping—the ability to connect a noisy technical component (a cluster, a database, a load balancer) to the business service it supports. | Second: ownership—the person or team accountable for that service and the chain beneath it. |

When you have those anchors, routing gets clean. Scope gets clean. The blast radius shrinks on its own.

Here’s the real-life version. You get an alert: “EKS node group degraded.”

That message can mean anything. Without context, it triggers panic. With a CMDB that models relationships, you can immediately see which services run on that node group—and which of those services are Tier-0 in production. Now your first page goes to the right owner, not the whole platform org. Your comms go to the right stakeholders, not everyone. Your mitigation targets the workloads that matter, not every workload that happens to exist.

In Cloudaware, this comes down to simple, practical mechanics: the cluster CI is linked to the services it supports, and those service records carry ownership and environment context. So you’re not doing a Slack scavenger hunt while the clock is ticking.

That’s the value. A CMDB doesn’t “solve incidents.” It removes the confusion tax, so your incident process can actually do its job.

CMDB in ITIL Problem management

Incidents are interruptions. Problems are causes.

In ITIL 4, Problem Management exists to stop “same outage, new ticket number” from becoming your company’s personality. But you can’t prevent repeats if you can’t connect the evidence. And most teams can’t—because the evidence lives in places that don’t line up: Slack threads, alert screenshots, someone’s hunch.

That’s where CMDB ITIL earns its keep.

A CMDB gives you an anchor: the configuration item. A CI is the thing you can point to—service, database, cluster, load balancer, network path—and say, “this is where the incident touched reality.”

When incident records are consistently tied to the same CIs, patterns stop being invisible. Recurrence becomes measurable. Root cause stops being a debate.

One clear example

Your org gets three “checkout timeout” incidents in six weeks. Each one is “resolved” fast. Restart pods. Add replicas. Everyone moves on.

Now link those incidents to the CIs involved, and the story changes. You notice every event includes the same dependency chain: the checkout service → database connection pool → shared NAT path during peak traffic. The pods were noisy. The shared dependency was brittle.

So the problem record becomes actionable:

- Problem statement: repeat timeouts tied to the same dependency chain

- Root cause clue: saturation on connection pool / network egress during peak

- Permanent fix: tune pool limits, increase NAT capacity, adjust routing, add safeguards

- Validation: no further incidents attached to those CIs after the change window

In Cloudaware, this is easier to execute because CI records already carry relationship context and owner fields, so you can follow the chain and land the fix with the right team—without running a detective agency in Slack.

How CMDB empowers ITAM

If you’ve ever tried to clean up assets in a hybrid environment, you know the trap.

The inventory is huge. The ownership is fuzzy. And “retire it” always sounds easy—right up until something customer-facing falls over.

That’s why ITIL CMDB software matters for IT asset management. Not because it gives you another list, but because it adds the two things asset work always needs: lifecycle state and accountability, tied to real service context.

The three questions ITAM needs answered every time:

1) What is it? (inventory)

2) Where is it in its life? (planned, active, end-of-life, retired)

3) Who is responsible? (owner/team, not “shared”)

When those answers live in the same record, ITAM becomes operational. You can actually run a retirement plan. You can enforce standards. You can stop paying for ghosts.

Here is an example of how it works in real life:

Security flags a set of compute resources as end-of-life. Finance is cheering. Ops is nervous. Without service context, the decision becomes a standoff. Nobody wants to be the person who decommissions the wrong thing.

With a CMDB, you do it like a grown-up:

- check lifecycle state and environment so you’re not touching prod by accident

- trace relationships to see what services depend on those assets

- route approval to the true owner, not the loudest channel

In Cloudaware, this fits neatly because discovered assets land with CMDB attributes (owner/team fields, environment, tags, lifecycle) and relationships that show what the asset supports.

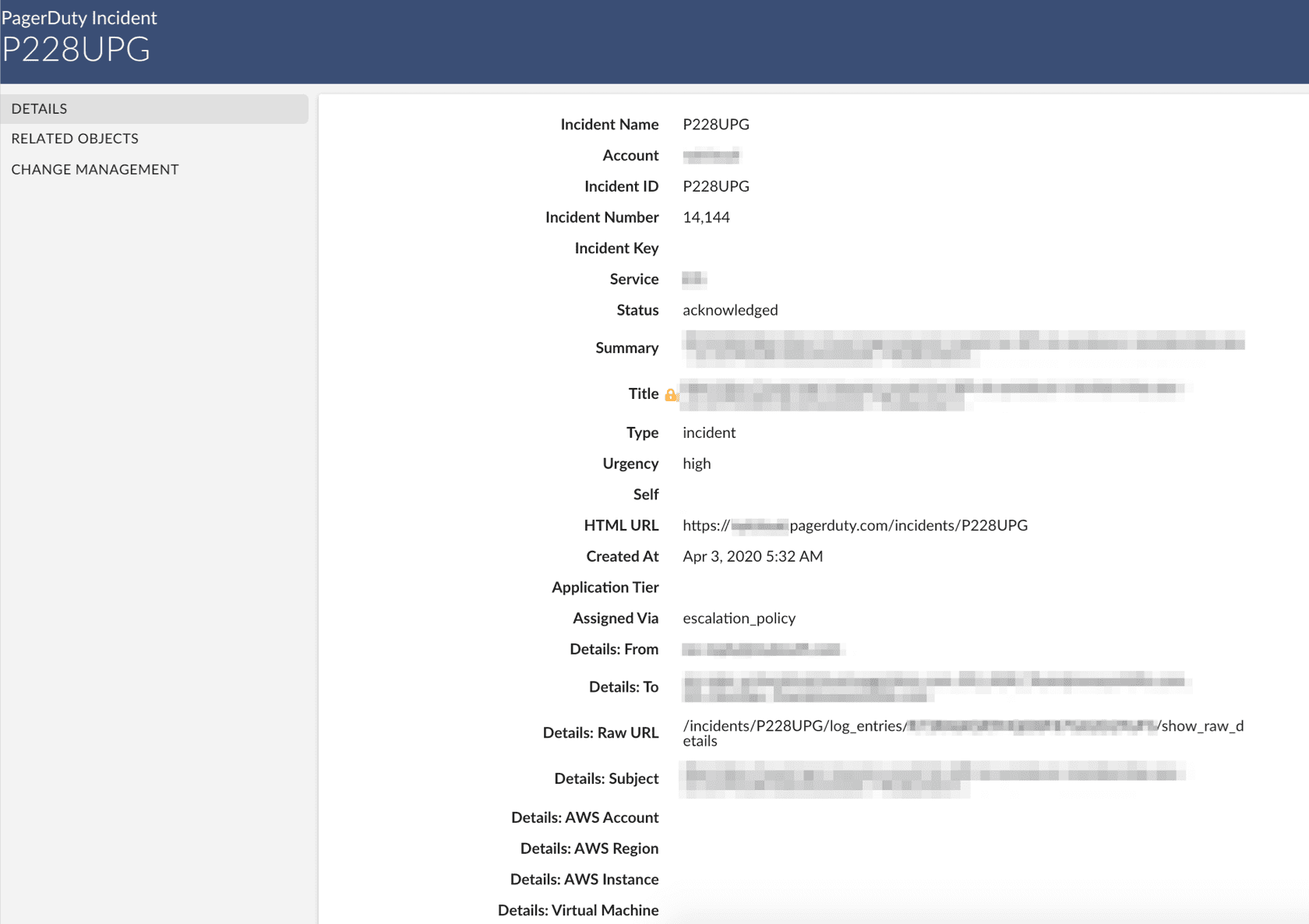

Sample ITIL incident in Cloudaware. Schedule a demo to see it in action.

So “retire” isn’t a guess. It’s a scoped change with accountability.

CMDB as a part of Information security management

Security teams don’t lose time because they can’t run a scanner. They lose time because nobody can agree on what to scan first.

That’s the everyday value of an ITIL CMDB in ITIL 4: it gives risk work a shared, defensible scope.

What “scope” really means in practice

In security and risk, scope usually comes down to two questions:

- Exposure: can something be reached from the internet, directly or through a public entry point?

- Regulated impact: does it support a regulated or business-critical service (PCI, HIPAA, Tier-0, customer data paths)?

If you can’t answer those reliably, every risk conversation becomes politics.

And every audit becomes archaeology.

The moment it clicks: risk is service-first, not asset-first

Most teams try to secure “all assets.” That’s noble. Also impossible.

The smarter move is to secure the services that matter most, then walk down their dependencies. That requires relationships: service → app → infra → network → identity.

This is exactly what a CMDB is built to model.

Here is how it works in real life:

A team ships a new microservice. They call it internal. Nobody worries.

A month later, an audit question lands: “Show every production component supporting Checkout that is internet-facing—or reachable through a public path.”

Without CMDB relationships, you start a scavenger hunt: cloud consoles, diagrams, tribal knowledge. Days vanish.

With CMDB relationships, you take a service-first path:

- start at Checkout (service record),

- traverse dependencies to the load balancer and network path,

- identify which components are exposed and which are in a regulated scope,

- assign ownership and remediation to the right teams.

Interested in ITIL CMDB software? Here is what to look for

If you’re shopping for ITIL CMDB software, you’re probably in the same spot most teams hit: the CMDB is “planned,” the audits are “soon,” and every incident bridge ends with “we don’t actually know what depends on what.” So you start the search.

And this is where people get burned. Demos look clean. Data looks perfect. Then you import your real environment and suddenly it’s duplicates, stale records, missing owners, and a dependency map that’s more wishful than factual. The tool wasn’t the problem. The lack of governance and data mechanics was.

Here’s what to look for if you want an ITIL CMDB you can trust under pressure—not just a database you can populate.

Must-have capabilities:

- Continuous discovery across cloud + on-prem, with predictable refresh cadence

- Normalization + de-duplication so the same asset doesn’t show up five ways

- Reconciliation rules (source-of-truth priority) to prevent data conflicts

- Relationship modeling that supports service context and impact analysis

- Ownership + accountability fields that are enforceable (not optional)

- Lifecycle states (planned/active/retired) with governance workflows

- Data quality reporting (freshness, completeness, orphaned CIs, duplicates)

- Integrations/APIs so changes, incidents, and evidence don’t live in silos

- Role-based access + segmentation (prod vs non-prod, accounts, tenants)